From the study by Clark, we give the table for 1780-9 to 1860-9, for skilled building craftsmen:

Building Wages, the Cost of Living and Real Wages by Decade, 1209-2003

| Decade | Craftsmen day wage (pence) | Craftsmen day wage (1780-9 = 100) | Cost of Living (1780-9 = 100) | Craftsmen real wage (1780-9 = 100) |

| 1780-9 | 26.3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 1790-9 | 29.8 | 113.3 | 116.3 | 97.5 |

| 1800-9 | 39.3 | 149.4 | 156.2 | 95.9 |

| 1810-9 | 47.4 | 180.2 | 174.8 | 102.8 |

| 1820-9 | 44.9 | 170.7 | 143.1 | 119.2 |

| 1830-9 | 45.2 | 171.8 | 129.7 | 132.7 |

| 1840-9 | 45.7 | 173.7 | 125.7 | 138.7 |

| 1850-9 | 47.7 | 181.3 | 119.3 | 152.4 |

| 1860-9 | 55.1 | 209.5 | 126.4 | 165.3 |

(extracted from: Clark, 2004, Table 4, p. 54-55; converted to 1780-9 index = 100 by this author)

As in the case of the unskilled workers in the calculations of Clark, we see that the real wages remain stable from 1780-9 to 1810-9, and then increase by 50 % to 1860-9.

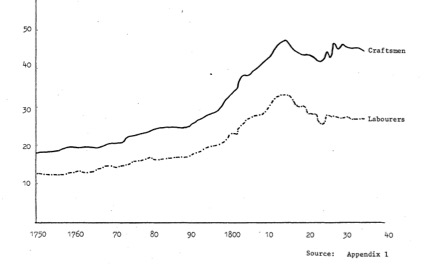

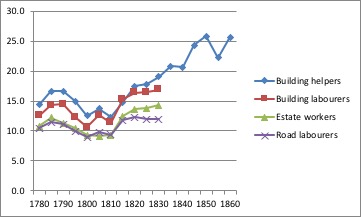

From the investigation referred to above, by B. Eccleston, we have the following movements for skilled building workers.

Fig. 9, Building Workers, mean wage rates

(Ecclestone, 1976, Fig. 9, p. 73)

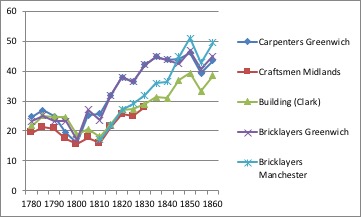

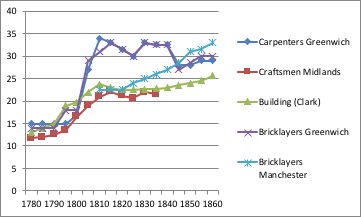

With reference to carpenters and bricklayers, we have continuous data from 1780 to 1860, from the contract prices of Greenwich Hospital. The wages are practically constant for the period 1780 to 1800, they are suddenly doubled in 1800, and then maintain this level until 1860. We might think that that this was due to a change in contractual conditions in the works in Greenwich, and thus not representative of the whole country. However there are similar movements in Macclesfield for joiners and bricklayers of 33 % from 1793 to 1815, and then without changes to 1838.

The carpenters in London in 1850 had a good standard of living. The better part, who had lived all their lives in London, and had contracts with the masters, had an income of about 30 shillings a week, while the lower class, those who had recently immigrated from the country, and had to look for work with informal builders, had an income of 20 to 25 shillings. The information in 1850 was that the wage level had not changed in 30 or 40 years.

“The more respectable portion of the carpenters and joiners “will not allow” their wives to do any other work than attend to their domestic and family duties, though some few of the wives of the better class of workmen take in washing or keep small “general shops”. The children of the carpenters are mostly well brought up, the fathers educating them to the best of their ability. They are generally sent to day schools. The cause of the carpenters being so anxious about the education of their children lies in the fact that they themselves find the necessity of a knowledge of arithmetic, geometry, and drawing in the different branches of their business. Many of the more skilful carpenters I am informed, are excellent draughtsmen, and well versed in the higher branches of mathematics. A working carpenter seldom sees his children except on a Sunday, for on the week day he leaves home early in the morning, before they are up, and returns from his work after they are in bed. Carpenters often work miles away from their homes, and seldom or never take a meal in their own houses, except on a Sunday. Either they carry their provisions with them to the shop, or else they resort to the coffee-shops, public-houses, and eating-houses for their meals. In the more respectable firms where they are employed, a “labourer” is kept to boil water for them, and fetch them any necessaries they may require, and the meals are generally taken at the “bench-end”, under which a cupboard is fitted up for them to keep their provisions in. In those shops where the glue is heated by steam the men will sometimes bring a dumpling or pudding and potatoes with them in the morning, and cook these in a glue-pot which they keep for the purpose. In firms where the glue is dissolved by means of hot plates small tins are provided, on which they cook their steaks, rashers of bacon, red herrings, or anything else that they may desire. These arrangements, I am informed, are of great convenience to the men, and in those shops where such things are not allowed they are mostly driven to the public houses for their food.”

The carpenters received their work through “houses of call” (which were in pubs), which had a roll-book of workers, where they would be assigned to a master or architect who required their services. They had common funds, which acted as friendly societies, and paid them in times of sickness or unemployment.

(Mayhew, 1850, Letters LX, LXI and LXII)

In Lancashire in the period 1839-1859, the bricklayers had an increase from 27 shillings to 33 shillings, and the bricklayers’ labourers from 18 shillings to 21 shillings (with a reduction in hours worked per week, from 60 to 55 ½). The brickmakers also increased their income, from 42 shillings to 50 shillings weekly.

(Chadwick, 1860, Section V, pp. 12 and 16)

Carpenters, joiners, bricklayers, stonemasons (shillings per week)

| Carpenters | Craftsmen | Building | Bricklayers | Bricklayers | |

| Greenwich | Midlands | (Clark) | Greenwich | Manchester | |

| 1780 | 15 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

| 1785 | 15 | 12 | 14 | 14 | |

| 1790 | 15 | 13 | 15 | 14 | |

| 1795 | 15 | 14 | 19 | 18 | |

| 1800 | 17 | 17 | 20 | 18 | |

| 1805 | 27 | 19 | 22 | 29 | |

| 1810 | 34 | 21 | 24 | 31 | 23 |

| 1815 | 33 | 22 | 23 | 33 | 23 |

| 1820 | 32 | 21 | 23 | 32 | 23 |

| 1825 | 30 | 21 | 23 | 30 | 24 |

| 1830 | 33 | 22 | 23 | 33 | 25 |

| 1835 | 33 | 22 | 23 | 33 | 26 |

| 1840 | 33 | 23 | 33 | 27 | |

| 1845 | 28 | 24 | 27 | 29 | |

| 1850 | 28 | 24 | 29 | 31 | |

| 1855 | 29 | 25 | 30 | 32 | |

| 1860 | 29 | 26 | 30 | 33 |

Carpenters, joiners, bricklayers, stonemasons (loaves per week)

| Carpenters | Craftsmen | Building | Bricklayers | Bricklayers | |

| Greenwich | Midlands | (Clark) | Greenwich | Manchester | |

| 1780 | 25 | 19 | 22 | 23 | |

| 1785 | 27 | 21 | 25 | 25 | |

| 1790 | 25 | 21 | 25 | 23 | |

| 1795 | 19 | 17 | 25 | 23 | |

| 1800 | 16 | 16 | 19 | 17 | |

| 1805 | 25 | 18 | 21 | 27 | |

| 1810 | 26 | 16 | 18 | 24 | 17 |

| 1815 | 32 | 21 | 22 | 32 | 22 |

| 1820 | 38 | 26 | 27 | 38 | 27 |

| 1825 | 36 | 25 | 27 | 36 | 29 |

| 1830 | 42 | 28 | 29 | 42 | 32 |

| 1835 | 45 | 31 | 45 | 36 | |

| 1840 | 44 | 31 | 44 | 36 | |

| 1845 | 40 | 34 | 39 | 41 | |

| 1850 | 46 | 39 | 47 | 51 | |

| 1855 | 39 | 33 | 41 | 43 | |

| 1860 | 44 | 38 | 45 | 50 |

Carpenters, joiners, bricklayers, stonemasons (shillings per week)

Carpenters, joiners, bricklayers, stonemasons (loaves per week)