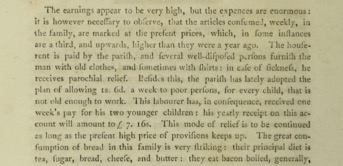

It is not true that the agricultural labourers’ families only ate bread, bacon or pork, and cheese, such as are shown with cost in the family budgets.

The majority of the poorer segment of the labourers had gardens next to their cottage, where they grew potatoes, cabbages, carrots, and other vegetables. In the worst months of scarcity, the potatoes could make up the half of the physical volume of food consumption.

A certain proportion of the labourers had a pig, which was fattened, and killed at the end of the year, to be converted into salt pork, which was then eaten through the following year; the costs are given in the family budgets (sometimes), showing the purchase of barley, peas, and beans for feeding the animal. Many labourers also had chickens, for eggs. Milk for children was sometimes given free to the poor villagers, by neighbours who had a cow.

After the men cut the wheat in the harvest, the next day, the small children of the village were allowed into the field at dawn, to pick up the individual seeds that had fallen to the soil (“gleaning”). The amount over the full harvest period each year might well be 2 to 4 bushels per family, that is, they saved two to four weeks of expenses for food.

In all the cereal parts of England, it was the custom that during the harvest month, the farmer sent food to the field where the men and women were working, together with a supply of beer. Thus the family did not have to pay the month of food. The day after the end of the harvest, there was a feast, called “Harvest-Home”, also paid for by the farmer; there was usually also a procession with a cart decorated with objects made out of wheat stems.

“The mode of living, or the kind of food provided for the men, varies considerably in different places. With some it is customary to give seed-cakes and ale for breakfast, as well as at wheat harvest-home, &c.; but in general, meat is allowed three times a day, which consists of pork, bacon, &c. with from one-fourth to one-third of butchers’ meat, and in general plum-puddings; and three meals on each of the four Sundays in the month. It is customary to allow three pints and a half of ale per day; viz. in the morning, at eleven o’clock, and at four in the afternoon; but in some places, the allowance of ale extends to four or five pints, and one pint per man on a Sunday. The evening of the harvest-home is, as is usual in most places, a scene of festivity, when the harvest men, their wives, and children, and other helpers and neighbours, compose a numerous and expensive assemblage. When the month is finished, the plum-pudding disappears, and daily pay is reduced about Lidlington, &c. to 1s. but remains in some places as high as 15d., and even 18d. with food and beer as before.”

(Board of Agriculture / Thomas Batchelor, General View of the Agriculture of the County of Bedford, 1813, p. 584)

“The Harvest Home” by Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827), painted 1821

But it is also not true, that the families only earned their money by working at agricultural tasks for the farmer. A considerable number, “cottagers”, rented a few acres, to grow their own wheat or to pasture one or more cows. The man would work six days a week for the farmer, and then work late at night or on Sundays on his own plot; the wife and the children would work on the fields during the week.

“ …. There are also a great many cottagers, by which I mean, occupiers of small portions of land, just sufficient to enable them to keep one or two cows, without preventing them from working constantly as day-labourers:- this custom does not prevail in all the parishes, but wherever it does, the benefit of it is felt by the cottagers themselves in the greatest degree, and by the proprietors and occupiers of the lands in the lowness of the poor rates, and in the industry and good order of that description of labourers. These small portions of land are generally well managed, and made the most of.”

(Young, Annals of Agriculture, Vol. XXII, 1794, Agriculture of Rutland, p. 355)

We do not know what percentage of labouring families were cottagers in this sense of the term. The Earl of Winchelsea, who was a friend of Arthur Young, and very interested in agricultural improvements, gave a list of eight different forms of working the land by the labourers. We may suppose that if these eight classes were important enough to be mentioned, it cannot be the case that more than 50 % of the families were in the position “8th”. Following we give the Earl’s heading for each type:

1st, Those who have a sufficient quantity of grass-enclosed land to enable them to keep one or more cows, winter and summer, and a garden near their house.

2dly, Those who have a summer-pasture for their cow, and some arable land, upon which they grow the winter provision.

3dly, Those who have a right of common for the summer keep of the cow, and a meadow, or arable ground, or a meadow in common, for the winter provision.

4th, Those who have a right of common and garden.

5th, Those who have a right of common, and no garden.

6th, Those who have several acres of arable land, and no summer pasturage for a cow.

7th, Those who have a garden near their house.

8th, Those who have no land whatever.

(“This is a very bad situation for a labourer to placed in, both for his comfort, and for the education of his children. When a labourer is possessed of cattle, his children are taught early in life the necessity of taking care of them, and acquire some knowledge of their treatment; and if he has a garden, they learn to dig and weed, and their time is employed in useful industry; ….”)

(Earl of Winchelsea, Lord Brownlow, Robert Barclay, Mr. Crutchley, Henry Holland, Robert Beatson, A. Crocker; Communications to the Board of Agriculture, on Subjects relative to the Husbandry and Internal Improvement of the Country, Vol. I, Parts I and II, Part II, Cottages, London, Board of Agriculture, 1797)

The Earl commented that “there are several labourers in my neighbourhood, who have got on in that manner, till they now keep two, three, and some four cows, and yet are amongst the hardest working men in the country, and the best labourers. I believe there are from seventy to eighty labourers upon my estate in Rutland, who keep from one to four cows each; and I have always heard that they are hard working industrious men; they manage their land well, and always pay their rent. With regard to the profit they make of a cow, I am informed that those who manage well, will clear about twenty-pence a week, or £ 6 6s. 8d. per ann. by each cow, …. “ (p. 78)

It seems that the greatest concentration of cottagers with rented fields was in Lincolnshire and Rutland. The Board of Agriculture was very interested to see if this method of farming could be extended – this was 1800, the year of the worst corn scarcity – so they sent a Mr. Robert Gourlay to inspect the area and make a report.

Starting in January 1801, he visited a number of villages in Rutland and Lincolnshire.

The first village listed is Belton. 24 families (83 family members) farmed rented land. The landowner, Lord Brownlow, allotted them a total of 150 acres for their farming activities. Note that all the men worked during the week for their farmer. They also rented cottages of a comfortable type from Lord Brownlow.

Mr. Gourlay was most impressed by the fact that, of all the people that he interviewed in the two counties, not one had had to apply to the parish for financial aid inthe previous year. And this despite the fact, that in all England there had been a great scarcity of wheat and increase in the price of food, such that many families were only surviving bacause they were receiving parish relief or donations from individuals. The poor rates, that is, the payments to the poor, financed by the taxes on property owners, were less than in villages without “cottagers”.

In total, Mr. Gourlay reported on 40 parishes, with a total of 9,058 inhabitants. 618 families with 2,783 family members were cottagers with cows. On average they rented 6 acres of land each, with 1.5 cows, 0.8 pigs, 1.8 sheep, and 0.2 horses. They paid 7 pounds a year as rent of the land.

(Mr. Robert Gourlay; An Inquiry into the State of the Cottagers in the Counties of Lincoln and Rutland; Annals of Agriculture, Vol. XXXVII, 1801, pp. 514-549 and pp. 577-600)

“Insuring Cottagers’ Cows

For some years past there has been a custom in Lancashire of insuring cows, paying 5s. a year and having the cow re-placed by the society, in case of death or accident. – It is an excellent institution; some gentlemen began it by subscribing 100 L. a piece, and all the rest an annual payment of 5s. Their annual payment, of late years, have so far exceeded the demand, that they have divided a good sum of their former subscription.”

(Young, Annals of Agriculture, Vol. 26, 1796, p. 501)

There was a further segment of cottagers, who did not rent the land which they would be working, but actually bought the land freehold, and built their cottage. The total cost between cost of land, payments for building the cottage, pig, cow, horse (in a few cases), and fencing, was about 50 Pounds. The question is, how did they pay for it? There were three ways: using the money they had saved up, as young men and women working as indoor farm-servants (bed and board free) or as apprentices, from 15 to 25 years old; living very economically, and saving the money during years as labourer; or making an initial payment, and contracting a mortgage.

Arthur Young visited a number of counties (Cambridgeshire, Norfolk, Essex, Surrey, Sussex, Lincolnshire) in the year 1800, and interviewed or informed himself about hundreds of families (not all the cases in his report are freeholders, some only rent). He was also interested in how the total of these activities could reduce the costs of rates to the parish.

(Arthur Young. An Inquiry into the Propriety of applying Wastes …….., 1801, whole document)

He was very impressed with the hard work and determination which the families had shown, in order to save up the money necessary, and then to work the fields while the father was working six days a week for the farmer (there is one account of the whole family harrowing their field by moonlight!).

“But the cases here detailed prove clearly, that wherever there is such a hope, it operates beyond all the powers of calculation. How these men were able to effect their object surpasses inquiry; that they saved money with this view is palpable, because in most of cases the erections have been the work of regular carpenters and masons, who could not have been employed without a considerable part of the expence being paid for; and this accordingly I found the case, for where mortgages had taken place, it was only for a part of the expence, in many instances for only a small part, and in some, not a few, without any such assistance at all.”

(pp. 9-10)

“Nothing can be clearer than the vast importance which all these poor people, scattered as they are through so many counties, and affected by circumstances so extremely various, attach to the object of possessing land, though no more than to set a cottage on.”

(p. 11)

“When we set by our fire sides and ask how a poor labourer can afford to build a comfortable cottage, enclose some land, break up and cultivate a rough waste, acquire some livestock, and get many conveniences about him, we defy calculation; there must be some moving principle at work which figures will not count, for in such an inquiry we see nothing but impossibilities. But we forget a thousand animating principles of human feeling. Such effects could not possibly have been produced without a series of years of great industry and most economical saving – to become independent, to marry a girl and fix her in a spot they can call their own, instigates to a conduct, not a trace of which would be seen without the motive ever in view. With this powerful impulse they will exert every nerve to earn, call into life and vigour every principle of industry, and exert all the powers of frugality to save. Nothing less can account for the spectacle, and such animating prospects will account for anything.”

(pp. 11-12)

Young talked to the wife of a Mr. Thomas Rich, who had been called up to the local militia. “… The woman (Rich) assured me, what is easy to believe, that she and six young children, and big of a seventh, none of whom earn anything regularly, should have perished, had not been for the great assistance derived from her land, which she has, in her husband’s absence, cultivated with her own hands, even to digging for sowing rye and wheat; her rye yielding four bushels and her wheat four bushels and three quarters. She had also cabbages, potatoes and other things.” [she did receive 10 shillings a week as compensation from her husband’s militia service] (pp. 92-93)

A typical information about a “success story”, among dozens, is Mr. Cranham of Waverley in Surrey. “Cranham, three children at home. Cottage built eight years, owes 19 l. on it, and eight years interest. It is of brick and tile, and has two stories. 2s. 9d. from the parish. A sow and four pigs. About an acre of good land in green-sward bottom. The woman thought a cow a fine thing, and would do anything to get one; but not much ability to calculate. Sowed three pecks of wheat this year, and got six bushels.” (p. 98)

Young was given information about a number of cottagers in the village of Blofeld in Norfolk, rich farming land, 2,000 acres, population 400, of which the half were cottagers with freehold. None of these had received assistance from the parish.

(pp. 60-61)

“In the Annals of Agriculture, No. 256, is an account by the late Sir William Pulteney of an occupation by a Shropshire cottager, Richard Milward, who with a wife and six children occupied 1 acre 10 perches of land, upon which, principally by the labour of his wife, the man being employed elsewhere, was raised annually 15 statute bushels of wheat, and 140 bushels of potatoes, of 80 lb. to the bushel, over and above the seed, and from which was supported and fatted a hog of 300 lbs. weight; in this case the odd 10 perch was cultivated for garden vegetables, and the acre in two divisions, wheat and potatoes alternatively, half an acre each; the manure raised from the hog by means of the wheat straw, and potatoe haulm [stem of the plant], being sufficient to support the crops.

The wheat was sown by the woman upon the following plan; in autumn, when the potatoes were fit to get up, she daily in the morning marked out the work of one day, upon the potatoe ground, from which she first cleared off the potatoe tops and haulm, this served to litter the pig and make manure, she then sowed that spot with wheat, and proceeding to get up the potatoes; the seed wheat was properly covered by that operation, and the wheat crop succeeded equally well or better than in any other way; they had formerly had it sown by the neighbouring farmers, but being frequently disappointed, had adopted this method, which had completely succeeded; and as the proper time of sowing wheat agrees exactly with that of getting up potatoes, namely the whole month of October, or any time then about the two operations are well combined in one; in this system an acre of land produces annually 15 bushel of wheat of 60 lb. each, 900 lb. consequently of bread …

900 lbs.

And potatoes 140 bushels besides seed for next year, at 80 lb. to the bushel …

11,200

The produce of wheat is more than the average, but may be obtained upon land well managed and kept clean from weeds, which in this case might be done by the wife and children; a clean crop of potatoes, is one of the best preparations for wheat.

An hog at one year old may grow to the weight of 300 lbs., and be supported to that weight from the above produce, and to spare; suppose his average allowance for the first three quarters of the year to be one peck of potatoes per day, besides refuse of wash and garden vegetables.

Suppose 270 days at 20 lb. per day of potatoes 5400 lbs.

90 days when fatting at 40 lb. per day 3600

9000

(Pitt, William; Communications to the Board of Agriculture, 1806, Vol. V, Part I, No. XVI, pp. 313-314)