The bad working conditions of the apprentice children in the mills in the Pennines, up to 1800, were described by Dr. Aikin:

“The invention and improvements of machines to shorten labour, has had a surprising influence to extend our trade, and also to call in hands from all parts, especially children for the cotton mills. It is the wise plan of Providence, that in this life there shall be no good without its attendant inconvenience. There are many which are too obvious in these cotton mills, and similar factories, which counteract that increase of population usually consequent on the improved facility of labour. In these, children of very tender age are employed; many of them collected from the workhouses of London and Westminster, and transported in crowds, as apprentices to masters resident many hundreds of miles distant, where they serve unknown, unprotected, and forgotten by those to whose care nature or the laws had consigned them. These children are usually too long confined to work in close rooms, often during the whole night; the air they breathe from the oil, &c. employed in the machinery, and other circumstances, is injurious; little regard is paid to their cleanliness, and frequent changes from a warm and dense to a cold and thin atmosphere, are predisposing causes to sickness and disability, and particularly to the epidemic fever which so generally is to be met in these factories. It is also much to be questioned, if society does not receive detriment from the manner in which children are thus employed during their early years. They are not generally strong to labour, or capable of pursuing any other branch of business, when the term of their apprenticeship expires. The females are wholly uninstructed in sewing, knitting, and other domestic affairs, requisite to make them notable and frugal wives and mothers. This is a very great misfortune to them and the public, as is sadly proved by a comparison of the families of labourers in husbandry, and those of manufacturers in general. In the former we meet with neatness, cleanliness, and comfort; in the latter with filth, rags, and poverty; although their wages may be nearly double to those of the husbandman. It must be added, that the want of early religious instruction and example, and the numerous and indiscriminate association in these buildings, are very unfavourable to their future conduct in life. To mention these grievances, is to point out their remedies; and in many factories they have been adopted with the true benevolence and much success. But in all cases the public have a right to see that its members are not wantonly injured, or carelessly lost.”

(Aikin, 1795, pp. 219-220)

Sir Robert Peel had observed that this conditions also obtained in his own mills, and did not like this situation. He managed to have a bill passed in 1802, which limited the hours for the apprentices to 12, and prohibited work at night.

As a result of the 1802 Act, in the following years magistrates or other classes of visitors were appointed to inspect the mills, to ensure that the apprentices were treated as the Act ordered, and the buildings were kept in a clean condition. The results of the inspections, which were not frequent, were collected in a document of the House of Lords in 1818.

“An Account of the Cotton and Woollen Mills and Factories in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland whereof Entry has been made at the Epiphany Sessions in Every Year from the Year 1803 to the Last Year ….

Appendix: Copies of Reports made by Visitors …..”

The reports in general gave positive valuations:

Appendix A, Chester, 1803, 2 mills, very satisfactory state, good ventilation, spacious rooms.

Appendix B, Chester, 1803, 5 mills, good conditions, ventilation, receive weekly wages, 12 hours work sometimes less.

Appendix C, Derby, 1802, 1 mill, 60 girls, “remarkable healthful and clean appearance”, writing and work in school.

Appendix D, Derby, 1803, Mr. Strutt at Belper and Milford, cleanliness of all kinds, work 13 hours with sufficient time for meals.

Appendix E, Derby, Wirksworth, 1803, 9 mills, incl. Cromford of Mr. Arkwright, as required by the Act.

Appendix F, Derby, Wirksworth, 1804, as previous, as required by Act.

Appendix G, various mills, unclear

Appendix H, Derby, Scarsdale, 1807, regulations strictly observed, “health, instruction, and morals of the apprentices receive a conscientious attention from the two resident proprietors”.

Appendix I, as E, 1807, as required by Act.

Appendix J, as E, 1808, as required by Act

Appendix K, 1811, Glossop and neighbourhood, 13 mills, all clean and whitewashed, but 1 dirty, Mr. Oldknow at Mellor: “any commendation of mine must fall short of Mr. Oldknow’s very meritorious conduct towards the apprentices under his care, whose comfort in every respect seems to be his study; they were all looking well, and extremely clean”; Mr. Litton at Needham: 15 hours work less ¾ for food, instructed in reading and writing on Sundays; Mr. Newton at Cressbrook: very comfortable, live well, 14 hours work less 1 hour food.

Appendix L, County of Lancaster, 1803, 12 mills, incl. Staylely Bridge, very good to indifferent.

Appendix M, Salford Hundred, 1803, 3 mills, require more ventilation.

Appendix N, Salford Hundred, 1803, 4 factories, cleanliness and ventilation highly satisfactory.

Appendix O, Ashton-under-Line, 1803, workers are not apprentices, no comments.

Appendix P, Todmorden, 1803, all the cotton mills, Act very well observed.

Appendix Q, Calderbrook, w/o date, 4 factories, 2 good 2 bad as to ventilation.

Appendix R, Lancs. Horton, 1803, all, conform to Act.

Appendix S, Walton-le-Dale, 1803, 5 mills, all good.

Appendix T, Goosnargh, 1803, 2 mills, all cleanly and wholesome, people orderly and regular.

Appendix U, Blackburn, 1803, one mill, clean.

Appendix V, Blackburn, Livesay, 1803, one mill, washed and ventilated.

Appendix W, Blackburn, Samlesbury, 1803, one mill, 45 apprentices, rooms clean, one suit of clothes per year, separate room for instruction in reading, writing and arithmetic in working hours, apprentices sleep 2 to a bed.

Appendix X, Horwich, 1803, no apprentices, no comments.

Appendix Y, Lancaster, Middleton, 1803, 2 mills, “remarkable good state of health”.

Appendix Z, Salford Hundred, Chadderton, 1803, one mill, agreeable to the act.

Appendix A.1, Eccles, 1804, 4 mills, “every thing highly satisfactory”

Appendix B.1, Barton, 1804, 1 mill, conducted according to the Act

Appendix C.1, Leyland, 1806, 2 mills, no apprentices, good ventilation and whitewashing

Appendix D.1, Manchester, 1810, Mr. Merryweather (Weaving Factory), Mr. Murray, Mr. Crowther, Mr. Gratrix, Mr. Mitchell, Mr. Pollard, Mr. Kennedy, Mr. Buchan, Mr. Birley, Mr. Marsland, Mr. Wilson; all cases insufficient ventilation, infrequent whitewashing, temperatures 75, no Rules put up. Mr. Merryweather’s mill: “The Potatoes for Dinner were boiling with the Skins on, in a State of great Dirtiness, and eight Cow Heads boiling in another Pot for Dinner; a great Portion of the Food we were told was of a liquid Nature; the Privies were too offensive to be approached by us; some of the Apprentices complained of being overworked.” Mr. Mitchell’s mill: “The apprentices appeared to us to be well-fed and clothed, and in a most comfortable situation.”

Appendix E.1, Nottingham, 1804, 6 mills, consonant to the Act.

Appendix F.1, Staffordshire, 1804, one factory, “much to our satisfaction”.

Appendix G.1, Reigate, 1805, one factory, “all is well”.

Appendix H.1, Reigate, 1806, same factory, “all is well”

Appendix I.1, Reigate, 1807, same factory, “all is well”.

Nearly all the boys and girls could read.

As to the inspections in Manchester in 1810, we see that the administrative part was absolutely insufficient, but in only one case did the apprentices complain, it appears that there was no gross mistreatment.

In 1817, 1818, and 1819, there were parliamentary hearings on the matter, which confirmed the reports of extremely bad conditions, particularly in Manchester.

On the other hand, a number of witnesses reported that, as an indirect effect of the 1802 Act, the infrastructure of the mills had been improved: “There has been a very great improvement in the condition of the mills; they are better ventilated, they are better heated, and the modern mills are more elevated in the rooms than the mills formerly were.”

(Select Committee on the State of Children….., 1816; William Sidgwick, cotton spinner, Skipton, Yorkshire; p. 114)

“Have you often been in the factories yourself?” “I have never been in them to visit them professionally; I have taken strangers and friends that have come from a distance through the mills, but my observation was not particularly directed to the health of the children; I have heard my friends frequently lament the looks and appearance of the children, how wretched their state was; and on inquiring how long they worked, and what they were subject to, they have regretted it particularly; ….”

(Reasons in Favour of Sir Robert Peel’s bill,…., 1819, Evidence of Dr. John Boutflower, p. 81)

“You have said you could point out the children in the streets; do you mean that in many instances where there were a number of children, you, as a medical man, were able to point out which child was employed in a cotton factory, and which not?” “I have pointed out such children, indeed, we generally know them, there is a peculiar cast in their countenances indicating general debility.”

“Did you fail in any of the conclusions you drew upon these occasions, or were you right?” “Perfectly right in every instance, and in adults the same.”

“And those instances were many?” “Yes, it was a subject of conversation; I have pointed them out, and said, Here is a factory face.”

(Reasons in Favour of Sir Robert Peel’s bill, …, 1819, Evidence of Dr. William Simmons, p. 86)

“You can hardly speak of them [his children] without crying?” “Yes.”

(House of Lords, Reasons in favour of Sir Robert Peel’s bill…., 1819, Evidence of Edward Francis, shoemaker, p. 58)

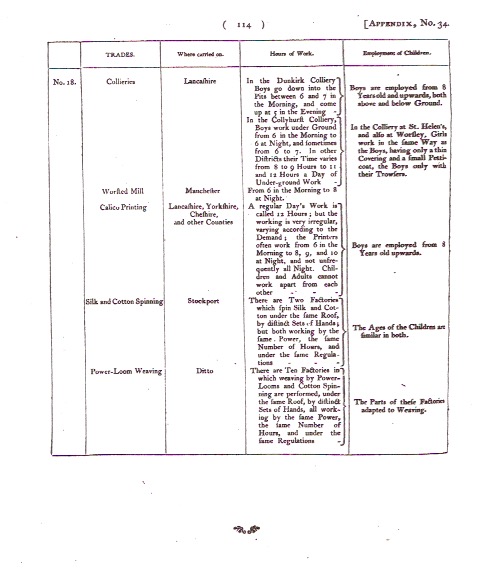

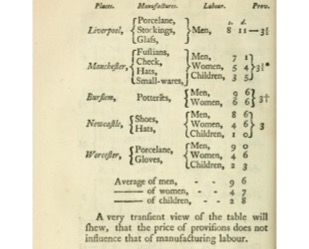

The bad conditions of work in the cotton-mills in Manchester, particularly from about 1815 to 1825, included:

- long working hours, from 13 to 16 hours, net of food breaks;

- often there were no food breaks, and the food had to be eaten standing;

- the children could physically not continue working all the hours, and were beaten to keep them awake, and continue with the work processes;

- the children had to clean the machinery after the contractual work-time;

- the men who were pushing the spinning mule backwards and forwards, had to do this continually through the day;

- the boys and girls (“piecers”) who accompanied the machine in its movements, walked at least 8 miles each day;

- the heat was extreme, particularly in the spinning of fine number, where it had to be 75º to 80º F;

- there was much cotton dust and small pieces of cotton (“flyings”) in the air, which got into the lungs;

- some of the moving equipment was not fenced off.

The effects of this maltreatment were:

- deaths of some children, from consumption of the lungs, or from exhaustion (some girls died before reaching puberty);

- deformation of the legs and spines of the children (some needed “irons” on the legs);

- the children suffered hunger;

- stunted growth of the children;

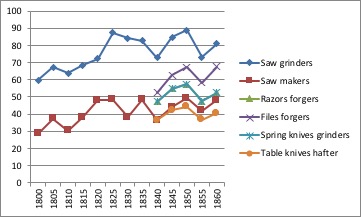

- the men were too physically exhausted to work at more than 40 years old;

- in winter, the men and children often had to leave the hot rooms at the end of the day, and go out into the cold air;

- for three-quarters of the days of the year, the adults and children, went to work and came back to their housing, in the dark;

- those who could eat enough food, ate it quickly, and thus is was not well digested;

- the children did not have any time or energy for schooling;

- breakages and amputations of fingers and arms;

- marks of scrofula on the cheeks and neck, due to the bad nutrition.

“Do you know any thing of the state of health of those children [factories in Manchester]?” “There are many there who look extremely ill indeed; I have had an opportunity of seeing them come in a morning, and they look very ill in a morning.”

(Select Committee on the State of Children…., 1816, Thomas Whitelegg, retired merchant, Visitor of schools, Manchester, p. 147)

“What is the general appearance of the children working in the factories, as to growth, health, dress, and cleanliness?” “In judging of children frequenting mills, by their size I have often taken them to be some years younger than they are, and the same remark has been made to me by others – generally speaking, their appearance is delicate, and less healthy than that of children confined to fewer hours of labour in the day; many of them, the younger children especially, are very badly clothed, and dirty. Upon the authority of a very experienced medical gentleman I state, that scrofulous complaints prevail very much amongst them, which he attributes chiefly to debility arising from excess of labour and confinement; and two other medical gentlemen asserted, that those complaints prevailed most in debilitated habits – the youngest children, moreover, from inattention and carelessness, often become crippled by being entangled in the machinery.”

(Select Committee on the State of Children….., 1816, George Gould, merchant, visitor Sunday Schools, Manchester; p. 98)

Dr. Boutflower of Salford is quoted that cotton factories are “a great national evil as they are conducted; that attending them checks the growth of young people, causes much disease, much deformity, particularly in the legs and knees, makes a short-lives puny race, promotes scrofulous complaints,”, “that of seven or eight thousand patients who are annually admitted to the Manchester Infirmary, one half of the surgical complaints are scrofulous.”

(Select Committee on the State of Children….., 1816, Nathaniel Gould, merchant, visitor Sunday Schools, Manchester; p. 328)

Zachariah Allen, a visitor from the United States in 1825, did not see these scenes of maltreated men, women, and children:

“When all the machinery of the cotton mills is simultaneously stopped at the usual hours of intermission, to allow the laborers to withdraw to their meals, the streets of Manchester exhibit a very bustling scene; the side walks at such times being crowded by the population which is poured forth from them, as from the expanded doors of the churches at the termination of services on the Sabbath in the large cities of the United States. On first beholding these multitudes of laborers issuing from the mill doors, I paused to examine their personal appearance, expecting to behold in them a sickly crowd of miserable beings, …. In this respect my anticipations were disappointed; for the females were in general well dressed, and the men in particular displayed countenances which were red and florid from the effects of beer, or of “John Barleycorn”, as Robert Burns figuratively called his favorite potion, rather than pale and emaciated by excessive toil in unwholesome employments in “hot task houses”. Every branch of business being in a prosperous state when I had an opportunity of noticing them, they may have appeared, perhaps, under favorable circumstances, and in the possession of more than their usual share of comforts and enjoyments. The children employed in the cotton mills appeared also to be healthy, although not so robust as those employed as farmer’s boys in the pure air of the open country.”

(Allen, Z., published 1832, referring to his visit in 1825, pp. 147-148)

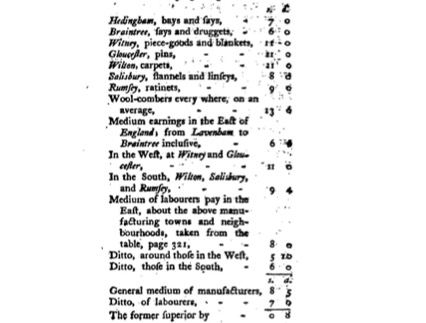

Following we have detailed information from Dr. Thackrah, who wrote the first book on occupational medicine, “The Effects of Arts, Trades, and Professions, and of Civic States, and Habits of Living on Health and Longevity”, in 1832. The book includes observations and measurements on about 100 occupations.

“COTTON-WEAVERS in large mills we remark to look better and be more healthy than the other operatives. At Manchester we saw 300 weavers, chiefly young women, at work in one room. This was, however, nearly three-fourths of an acre in area, well ventilated and lightsome. Scarcely any dust is produced by the weaving of cotton.”

(Thackrah, 1832, p. 37)

“COTTON-WORKERS, persons I mean who are employed in the several processes by which the plant is formed into yarn for weaving, are subject to considerable heat, and to some injurious agencies. I shall first refer to the process and operatives as I found them in a large mill at Manchester, and one, I believe, of the best conducted. In the first process, the machining, or cleaning and opening the cotton, no increase of temperature is required; the labour is light; the operatives are not crowded, nor is there any defect in ventilation. …. The children in this room made no complaint. The oldest man in it had been 16 years at the employ. He was thin but not sickly.

In the carding and preparing room the temperature is above 60°, a heat necessary to the working of the cotton and the machinery. The dust is not great; the labour is light, and the operatives are not crowded. The children, however, are puny. Head-ach [sic] and gastric disorders are frequent, especially among beginners. …..

In the spinning rooms the temperature is 60° to 70°. Particles of cotton float like thistle-down, but there is little dust. The machines are small, and the muscular exertion is good. In the dressing department, where the paste is applied to prepare the material for weaving, the heat of the room is greater than in any other process. We found it 98°, but were informed that it is generally rather higher. The men, however, appear healthy. Some complained of “aching of the bones”, but serious disease is rare except as a result of intemperance. They do not experience inflammation of the lungs, pleurisy, or rheumatism. There are few examples, however, of the men at the employ as old as 58.”

(Thackrah, 1832, pp. 144-145)

“I stood in Oxford-row, Manchester, and observed the streams of operatives as they left the mills, at 12 o’clock. The children were almost universally ill-looking, small, sickly, barefoot, and ill-clad. Many appeared to be no older than seven. The men, generally from 16 to 24, and none aged, were almost as pallid and thin as the children. The women were the most respectable in appearance, but I saw no fresh or fine-looking individuals among them. And in reference to all classes, I was struck with the marked contrast between this and the turn-out from a manufactory of Cloth. Here was nothing like the stout fullers, the hale slubbers, the dirty but merry-faced pieceners [i.e. at Leeds, where Dr. Thackrah was resident]. Here I saw, or thought I saw, a degenerate race, – human beings stunted, enfeebled, and depraved, – men and women who were not to be aged, – children that were never to be healthy adults. It was a mournful spectacle. On conversing afterward with a mill-owner, he urged the bad habits of the Manchester poor and the wretchedness of their habitations as a greater cause of debility and ill-health than confinement in the factories; and from him and other sources of information, it appears that the labouring classes in that place are more dissipated, worse fed, housed, and clothed, than those of the Yorkshire towns. Still, however, I feel convinced that independently of moral and domestic vices, the long confinement in the mills, the want of rest, the shameful reduction of the intervals for meals, and especially the premature working of children, greatly reduce health and vigour, and account for the wretched appearance of the operatives. To establish or correct this opinion, I afterwards examined a cotton-mill at Thorner, a village in an agricultural district, and where there is no other manufactory. Here, though the children had a somewhat better appearance than those at Manchester, they were decidedly more sickly in countenance and figure than the operatives in cloth-mills, and still more decidedly, than the peasantry around them. Though the temperature in this mill was not so high as those of Manchester, the air was more oppressive and ventilation less regarded. We had no reason to believe that either at these places or at the Leeds mill examined before, urgent diseases are often produced or the immediate mortality great. Disorders of the nervous and digestive systems are frequent, but not severe.”

(Thackrah, 1832, pp. 145-147)

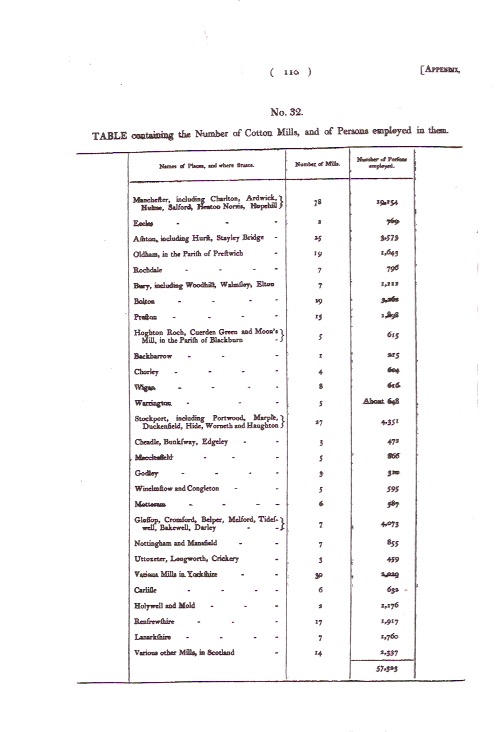

Possibly the morally worst aspect, was the employment in these difficult conditions, of children under 9 years old. The ages of the totality of persons working in a selection of cotton mills in Manchester, at the time of the 1819 investigation, were:

| 80 | under 9 years old |

| 764 | from 9 to 11, both inclusive |

| 1271 | 12 to 15, ditto |

| 781 | 16 to 19, ditto |

| 715 | 20 to 24, ditto |

| 533 | 20 to 24, ditto |

| 317 | 30 to 34, ditto |

| 211 | 35 to 39, ditto |

| 196 | 40 to 49, ditto |

| 70 | 50 and upwards |

| 4938 |

(Observations as to the ages of persons employed….., 1819, p. 3)

The situation a few years earlier was much worse, as the ages of these people when they went into the mills, was much lower.

| 1658 | under 9 years old |

| 1667 | from 9 to 11, both inclusive |

| 770 | 12 to 15, ditto |

| 371 | 16 to 19, ditto |

| 253 | 20 to 24, ditto |

| 122 | 25 to 29, ditto |

| 47 | 30 to 34, ditto |

| 26 | 35 to 39, ditto |

| 21 | 40 to 49, ditto |

| 3 | 50 and upwards |

| 4938 |

(Ibidem, p. 4)

There is a table from the same document, of “Ages in first going to a Cotton Mill”

| 5 | 5 ½ | 6 | 6 ½ | 6 ¾ | 7 | 7 ¼ | 7 ½ | 7 ¾ | 8 | 8 ¼ | 8 ½ | 8 ¾ | Total |

| 3 | 3 | 35 | 19 | 1 | 94 | 1 | 30 | 1 | 131 | 2 | 20 | 4 | 344 |

Report from Messrs. McConnel and Kennedy’s factory, of 1115 persons employed

(Ibidem, p. 16)

“The inference [from the preceding tables] therefore is, that of 4466 persons who begin their labours in a Cotton Mill at all ages under 20, only 1573 who arrive at their 20thyear continue to be engaged in the business.”

(Ibidem, p. 10)

“… The question instantly arises, What must be the fate of a great majority of the children brought up in Cotton Mills? For it is most evident that only a small proportion of those who do not die young can be continued in the business when they are grown up. The difficulty of their obtaining any other employment is well known; and might, indeed, have been presumed from merely reflecting, that their constitutions are generally enfeebled, that they have been habituated to no other business, and are, for the most part, in all other respects, extremely ignorant. Neither can it be said that they have any reasonable hope of obtaining, or, if obtained, of holding, for any length of time, those advantageous situations in the Factories occupied by grown-up people; …..”

(Ibidem, p. 10)

There is however a certain contradiction between the obvious physical exhaustion of the men, women, and children, and their activities outside the factory. One would suppose that the men would not do anything on Saturday night and during Sunday. But not only did they go out drinking, they also had time and energy to carry out a lot of union and radical political activities (See Foster, 1974, Table 8, pp. 145-146 for a list of about 45 working-class leaders 1795-1830). A certain number went to classes in the Mechanic’s Institutes; see the chapter on other activities.

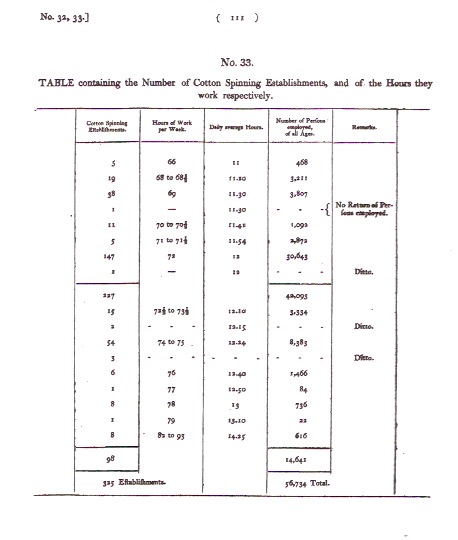

It seems that the bad treatment and the bad positions in the work decreased considerably from 1819 to 1833. Also the hours of work were in some cases reduced to 12 per day, plus time for eating. The work rooms in new factories were made with higher roofs and better ventilation, the work places and the cottages (in about 25 % of the mills, the adults and children lived in buildings which were property of the mill-owner) were whitewashed annually. The design of new machinery in some cases made the work less strenuous. About 30 % of the mill-owners reported that the health of the workers and children had improved in the ten years up to 1833. The main problem was still the long hours for the children; practically all the mills worked 69 hours the week of six days, plus time for meals.

The mill-owners of 1833 were convinced that the children and the adults in their factories were well treated. In a number of cases, they lived without charge in cottages nearby, they had rooms in the factory for eating and for changing their clothes on arrival and departure, and could regulate the ventilation themselves. But on the other hand, the owners were also absolutely convinced that it was not dangerous for the health of the children to work 12 hours a day, especially as in many cases the work was not physically tiring. See the 900 answers of the mill-owners to the questionnaires previous to the Factory Act of 1833: Factories Inquiry Commission, Supplementary Report, 1834, Part II.

To make a judgement as to the conditions in which the children were working in the cotton factories in the year 1833, as represented by the reports and inspections made for the Factory Bill 1833, we may take the resumed data given by Charles Wing in his “Evils ofthe Factory System, demonstratedby Parliamentary Evidence”. Mr. Wing was Surgeon at the Royal Metropolitan Hospital for Children, and dedicated his book to Lord Ashley (later Lord Shaftesbury). It is clear that he was on the side of the reformers. His digest (pp. xx-xxxvii) gives information in the following división:

The regular hours of labour. The time allowed for meals. The extra hours of labour. The age at which children begin to work. The nature of their employment. The state of the buildings in which that employment is carried on. The treatment to which the children are subject. The ultimate effects of their employment on their physical condition.

The regular hours of labour. In Scotland, in general from twelve to twelve and a half. In the North of England, generally twelve. In the Western district, do not exceed ten. These hours are exclusive of meals.

The time allowed for meals. In Scotland, half an hour for breakfast, half an hour for dinner, no stoppage for tea. In the North-East, half an hour for breakfast, one hour for dinner, half an hour for tea. In the Western district, one hour for breakfast, an hour for dinner, half an hour for tea.

The extra hours of labour. It is not an unusual practice, for the workpeople to use part of the dinner hour to clean the machinery. Time for additional production is paid proportionally.

The age at which children begin to work. The majority begin work at nine years old, and a few at lesser ages. Some branches of manufacture do not employ children at under ten years.

The nature of their employment. The types of employment do not, as such, cause health problems, providing the hours are sufficiently limited. But the continuous work with the machinery, the erect posture, and the lack of sleep have deleterious effects on the mind and body. Even light work, when carried out for an extreme number of hours, can damage the health. In many cases, in the factories, the children have to walk a large distance of miles each day.

The state of the is buildings in which that employment carried on.The old and small mills are dirty, low-roofed, ill-ventilated, no separate conveniences, machinery not boxed in. The large and recent constructions have better ventilation, higher roofs, little danger to the workers from the machinery. In all cases the sanitary installations are very bad.

The treatment to which the children are subject. There are many factories in which corporal punishment is strictly forbidden. In the smallest mills (particularly in Scotland and Eastern England) there are a number of cases of violence, usually inflicted by the adult worker on his child helpers. Many witnesses testify that formerly there was a great deal of “strapping”, but very little now.

The ultimate effects of their employment on their physical condition. Many children have severe pains in the legs and back, and suffer from extreme fatigue. The constant standing, and the abnormal positions in the work station, together with the elevated temperature, and the congested atmosphere, all cause considerable damage to the body. In the worst mills, there are also accidents caused by errors in the use of machinery, which cause mutilations.