So what was the reason that the weavers’ incomes went down, particularly starting in 1817? The principal cause was the large-scale export of “twist” (cotton yarn). This export had been subject to a duty, which was reduced gradually from 1810 to zero in 1820. At the same time (1814), the Wars with France had terminated, so that the whole Continent was now open to English trade. This changed the competitive situation of the English exporter of cotton cloth to the Continent, with respect to the French, German or Swiss producer of cloth.

Before, the English exporter had spinning costs in base of efficient machinery, and weaving costs in base of manual weavers’ looms; the foreign producer had spinning costs in base of spinning wheels, and weaving costs in base of manual weavers’ looms, the total of the two foreign costs was higher than the English costs. When the “twist” began to be exported in large amounts, to be used by continental weavers, the foreign producers then had spinning costs in base of efficient English machinery, and weaving costs in base of own manual weavers. Thus, in order to export to the Continent, the English manufacturers had to reduce their export prices considerably, which meant “squeezing” the piece payments to the weavers. But the continental weavers had lower incomes and lower living standards than the English weavers. Thus the incomes of the English hand-loom weavers had to be reduced to the nominal levels of those of the foreign weavers. But, unfortunately, they still had to buy their bread at English market prices.

We have a detailed explanation in 1823 by Richard Guest, cotton manufacturer:

“By these improvements in spinning the price of yarn was so much reduced, that the manufacturers were enabled to undersell their continental rivals, and at the same time could afford to remunerate the weaver with wages of thirty shillings per week. This was the case more particularly in the muslin manufacturers.

The twist and weft spun on the Water Frame and the Jenny are coarse, and are chiefly used for strong goods, for thicksetts, velveteens, fancy cords and calicoes. These goods were also manufactured in France, Saxony and Switzerland, from yarn spun on the hand wheel, the low price of labour in those countries, in some measure counterbalancing the advantages the English derived from their improvements in spinning; but in the manufacture of fine Muslins, the English had not a rival in Europe. The French, Saxons and Swiss, could not spin the yarns for the muslins on the hand wheel, and for some years, the English had the manufacture entirely to themselves. The continental manufacturers, however, soon procured fine yarns from England, and, with the aid of these yarns, they were enabled to rival the English in manufactured goods. By exporting mule yarn, the English have nourished and supported a foreign cotton manufacture, equal in extent to three fifths of their own, and have materially injured the interests of their own weavers. On the Continent, the necessaries of life are cheaper than in England, and the wages of the weavers very low, consequently, while foreign weavers are supplied with the same description of yarns the English manufacturer uses, obtained at the same price at that which he pays for them, he is compelled to reduce the wages of his own weavers to the foreign standard, in order to avoid being undersold in the market.

The machinery of England, particularly in the instance of the Mule, has thus been auxiliary to the prosperity of foreign, and generally, hostile nations. It has created resources of revenue for their treasuries, and a population to supply their armies, and, at the same time, has proportionally impoverished and injured its own. That this is not an exaggerated position, will be evident from the following extracts from Parliamentary returns of the quantity of twist exported:-

In 1816, ……… 16,362,782 lbs. were exported.

1818, ……… 16,106,000

1819, ……… 19,652,000

1820, ……… 23,900,000

1821, ……… 23,200,000

1822 .. ……. 28,000,000

The twist and weft spun in Great Britain in the year 1820, may fairly be estimated at 110,000,000 lbs.

The twist exported from Great Britain in the year 1820, according to Parliamentary returns, amounted to 23,900,000

The lace, thread, and stocking manufacture use annually 7,000,000

Manufactured into cloth in Great Britain in 1820 79,100,000

One half of the seventy-nine millions manufactured in Great Britain, was twist for the warp, the other half was weft. Thus, for the sake of round numbers, we may say, that in 1820, Great Britain manufactured forty millions of lbs. of twist, and exported twenty four millions. The export of twist being as three, and its home consumption as five, it follows, that to every five cotton weavers employed in Great Britain, there are three foreign weavers supplied with twist for their warps by our exports. The foreign manufacturers in general spin their own weft. The number of cotton weavers in Great Britain cannot be less than three hundred and sixty thousand, and with their families, they are probably half a million. The whole number of persons employed in Great Britain in spinning for the foreign weavers in the year 1822, taking the export at 28 millions of lbs., could not exceed thirty-one thousand, of which number twenty thousand were children, and the twenty-eight millions of lbs. of twist, spun by them, furnished twelve months supply of warps for upwards of two hundred and fifty thousand of foreign weavers.

The individuals in Great Britain interested in the export of twist, and benefitted by that export, are as thirty-one, and with their families are as forty-six, the operative weavers in Great Britain, with their families, injured by that export, are as five hundred – what an astounding difference!- the interests of five hundred thousand people sacrificed to those of forty-six thousand! ……

…….

The evil of creating a colony of foreign weavers by the unrestricted exportation of our own fine twist, must have been evident to all, and the bad consequences which it has caused, as well as those which may come, (and from the above details of the exportation of mule twist they are evidently considerable and increasing) are, on the score of neglect, justly chargeable to the Government of this country.

English twist was first exported in small quantities about the year 1790. At that time the continental weavers were chiefly employed in the manufacturing of linen and woollen cloth, and the English, by their improvements in spinning, possessed almost a monopoly of the cotton manufacture. The Continent, if left to itself, would not have attempted to vie with us in the article of cotton, and whatever may be said as to the high price of a manufacture in a particular quarter having a tendency to make the means of producing it emigrate from the soil of its birth, it is plain, that from the want of machine-makers, of trained and experienced workmen, of capital and of fuel, in foreign countries, a restrictive impost in the outset would have preserved to us those advantages which are now enjoyed by foreigners. Improvements in machinery and skill in the operative workmen are progressive, and in 1790 we were in both so far advanced beyond all the continental nations put together, as to leave them scarcely the chance of success if they had attempted to rival us. By means of their agents sent over for the purchasing of twist, they have now acquired a knowledge of our machinery, and have many spinning factories; these are chiefly employed in making weft. The twist for their warps, which requires better machinery, and greater nicety and skill in spinning than weft, is supplied by the English.

Under the dynasty of Buonaparte, the Continent was shut against us, and the quantity of twist exported from England was but small. When he was sent to Elba, in 1814, the Continent was thrown open, twist was exported without restriction, and, in succeeding years, in increased quantities. What followed? A reduction of the wages of our weavers (*), and its constant attendant, an increase of our Poor Rates.

If the Government of this country had paid proper attention to this subject, when twist was first exported, or in 1814, when the Continent was thrown open, great numbers of Weavers would have been kept off the Poor Rates, and probably much of the misery, tumultuous assemblages and riots, which took place in 1819, would have been prevented.

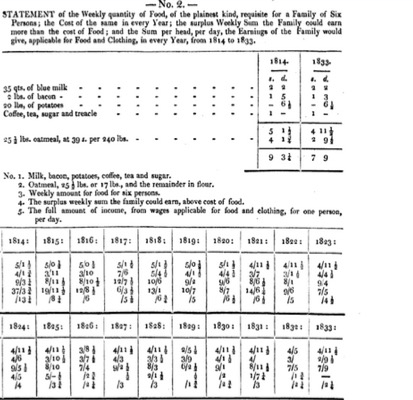

(*) Prices paid for Weaving 6-4ters, 60 Cambrics, 24 yards, 160 picks in an inch

s. d. s. d.

1800 31 6 1811 16 0

1801 30 0 1812 18 0

1802 32 6 1813 June 21 0

1803 June 34 6 November 27 0

December 28 0 December 32 6

1804 26 0 1814 June 28 0

1805 January 28 0 December 20 0

August 32 0 1815 17 0

1806 January 30 0 1816 January 17 0

June 27 0 June 14 0

December 26 0 1817 14 0

1807 April 22 0 1818 14 0

December 18 0 1819 12 0

1808 18 0 1820 12 0

1809 February 18 0 1821 13 6

June 20 0 1822 12 0

1810 March 25 0 To weave one of these pieces would

December 19 0 occupy a weaver about a week.

From the above table it will appear, that ever since the years 1815 and 1816, when the Continent was opened for the reception of British Twist, the Wages of the English Weaver have gradually declined.”

(Richard Guest, A Compendious History of the Cotton-Manufacture, Joseph Pratt, Manchester, 1823; pp. 32-34)

“Do you think that the export of cotton twist to the continent has been the great means of lowering the wages of the weavers since the peace?” “I consider it to have been a great mistake in our commercial policy, to have allowed the exportation of cotton yarn.”

(Select Committee on Hand-Loom Weavers Petitions, 1834, evidence of Mr. John Makin, Manufacturer, Bolton, p. 411)

Other factors which depressed the wages in the cotton weaving industry in the period from 1816 to 1820 were:

- the return in 1815 of 400,000 men from serving in the Armed Forces, many of whom could not find a job;

- immigration of Irish workers;

- the return to legal course of paper money, not just coin, after the Wars (“Mr. Pitt’s Bill”), but on conversion terms which were equivalent to a deflation.

“Hand-loom weaving, in short, has been, and is, a receptacle for the destitute from all other classes, and the great, the really appalling evil is, that the labour of the parent, once transferred to the child, what is found to be child’s work, comes to be rewarded with child’s wages.”

(House of Lords, Hand-loom Weavers, 1840, pp. 581-582).