HEIGHTS IN ENGLAND IN THE LATE EIGHTEENTH AND THE NINETEENTH CENTURIES

“It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.”

Sherlock Holmes, A Scandal in Bohemia, Arthur Conan Doyle

By far the longest-running difference of opinion about a historical process has been the “Question of the Condition of England”, that is, whether the population of England had an improvement or a deterioration in their living standards in the period of the Industrial Revolution from about 1770 to 1860. The expression “living standards” is taken to include, or more exactly to be the net effect of: wages, food consumption, working conditions, health, mortality, sanitation, and housing. But we cannot calculate the net effect of these factors, because we do not have objective time series of any of these before 1840; particularly this is true of wages and food, for which we have a few figures, but we do not know how to form an average value for all the classes and types of employments.

On the other hand, even if we had these series of numbers for each factor, we would not be able to quantify the net effect of these on the body or on the feelings of the persons. However, we may reasonably suppose that this net effect would be shown by movements in the heights of the people. This is the idea behind “anthropometrics”.

It might appear that there would be a definite effect in this sense, as a certain proportion of people (men, women, children and young children) had physical afflictions, were affected in their growth, did not eat enough, or were weak. On the other hand the people in the industrial districts had a higher income and ate more. The data about movements in heights might well help us to understand what was the effect of the Industrial Revolution.

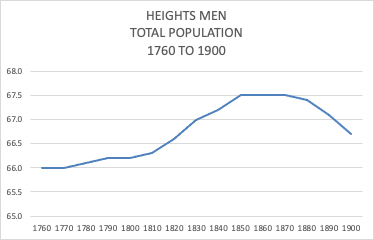

| The main conclusions of this investigation are: – The average height of men in the period 1780-1820 was from 5 ft. 6.0 in. to 5 ft. 7.0 in., and in 1850-1880 was from 5 ft. 7.0 in. to 5 ft. 8.0 in.; – The men and women in the nineteenth century were not absolutely of low stature, but were of the same height as were adults at the time of the Second World War; – The yearly average heights of Army recruits in Great Britain cannot be used to estimate the heights of the general population, as they moved only as a function of war/peace situations, and of military-administrative decisions; – In the period of 1880 to 1900, there was a “slum class” with a stature of 4 inches less than the normal population, which may have reached 20 % of the city populations, and thus reduced the average height in the country by 0.8 inches. |

The general graph of male heights from 1760 to 1900 is as follows:

The detailed conclusions of this investigation are:

- There was no “stunting” of men due to insufficient food or bad health conditions, but there were cases due to extreme work quantity in some occupations;

- The first information about average heights of the working class (from 1882) states that the factory classes were about 1 ½ inches shorter than the average male, and that this was due to the fact that the machines did all the work, and thus the men had little physical exercise;

- The average for women was from 5 ft. 2 in. to 5 ft. 3 in., also with little annual movement (but we have little data);

- The boys and girls in the factories in the 1830’s were not stunted, but were of the same height as the children who did not work in factories, and the same height as those in Belgium (where there were few factories);

- Skeletons from burial grounds from 1750 to 1850, and measured in archaeological excavations, have an average height per burial ground of 5 ft. 6 ½ in. to 5 ft. 7 ½ in.;

- The average height for male convicts (incl. transportees to Australia) was from 5 ft. 5 in. to 5 ft. 6 in., with a minimum about 1830 to 1840 (birth year); the convicts were from 1 to 2 inches shorter than the general population, because they were typical of the working class;

- The average height for women convicts was from 5 ft. 1 in. to 5 ft. 2 in., with the same minimum;

- The men who went into the Army, were those who had problems of a personal sort, and were generally without hope of employment or food, that is, they were not “volunteers” in the usual sense of the term;

- The Army usually had problems to find enough recruits in each year;

- The average yearly heights of recruits in this period were from 5 ft. 5 in. to 5 ft. 8 in, but these were generally affected by one of: wars (high recruiting volume required, and thus abandonment of minimum height standards), movements in minimum height standards, payments of signing-on bonus, military budgets;

- The average height for the totality of the “recruit-giving class” segment for the period 1800 to 1875 was close to 5 ft. 6 in., without any change over the years;

- Data from the “Floud investigation” showing average heights of 5 ft. 8 in. to 5 ft. 10 in. for the years 1760 to 1800 are misleading and not useful, as they refer only to members of the Artillery, who were taller and stronger than the infantry;

- In the years 1880 to 1899, the Army had great difficulty in finding recruits of the required height and strength, as they were receiving the majority of their recruits from slum areas.

A comparison with present height figures certainly is useful, as it does help to give an idea of the persons we would have seen «walking along the street». But if we wish to evaluate if the men were particularly short, due to their living and nutritional situation, we should use the year e.g. 1950 as a base point, and not 1990 or 2020. It is not the «fault» of the men of the 19th century, that there was a considerable improvement in nutrition and in health in the second half of the 20th century. The heights were/are: 1810 = 5 ft. 6 1/2 in., 1840-1880 = 5 ft. 7 1/2 in., 1950 = 5 ft. 7 in., 1990 = 5 ft. 8 in., 2020 = 5 ft. 9 1/2 in.

The definition of the World Health Organization for «stunting» is more than two standard deviations below the average of the general population at the given age». The only groups which might be in this case, would be the silk weavers in Spitalfields, the nail- and chain-makers in the Black Country, the framework knitters (hosiery) in the Midlands, and the slum dwellers in London and the Northern Industrial towns from the year 1880 onwards. The coal miners were short, but with a muscular torso.

It is important to note, when we are investigating if the bad living conditions in the country left a mark in the bodies of the people, that the Industrial Revolution did not start on a large scale in these terms, before 1800. Manchester had only 90,000 inhabitants, of which 13,000 worked in the cotton mills, and not all lived in bad accommodation. Leeds was still livable, there was little overcrowding; the population started increasing in 1820, and doubled by 1840. In Leeds, there was practically no spinning machinery before 1820. In Bradford, there was no spinning or weaving machinery before 1810, the year in which the first spinning frames were installed in buildings; the population of Bradford in 1811 was 60,000. In Birmingham, all the families lived each in a separate house, and there were no inhabited cellars.

Soldiers’ heights from regimental records, and analysis for anthropometric considerations.

There are academic investigations on the subject, but some of the conclusions have to be handled with care. The academic studies gather information about convicts and soldiers, as these were under the control of the authorities, and thus were long-term data about the heights. The registers of average annual heights taken from European armies give us dependable data for the average heights of the total male population, as practically the whole number of the population was called up each year; thus there was a continuity in the data as to stature which reflected changes in the real world in each country. In Great Britain, the recruits were “volunteers” (more exactly, they were usually unemployed men who needed a job that would give them food, bed, and guaranteed – although low – wages). They were only a small proportion of the population, and thus it is difficult to extrapolate to a figure for the whole population. Further, the number that applied each year, and the average height of these, was affected by the war/peace situation, and the state of the jobs market.

The other complication for the British Army recruits, is that the Army used “minimum height standards” to accept the men, and that these standards were changed from time to time. In Europe, these minima did not change much. Thus it is complicated to calculate consistent yearly average heights for the “recruit-giving class”, that is, the segment of the working class that would be interested in applying for the army, but including those above minimum heights and those below minimum heights, and those physically fit, and those not physically fit. As a final step, the adjusted heights for each year have to be regressed to the data of birth of each recruit, as the theory tells us, that the adult heights are a function of the wage, food, and sanitary conditions in early childhood.

The major study about British soldiers is that of Roderick Floud, Kenneth Wachter, and Annabel Gregory, published in 1990 (“Height, Health and History”), utilising a data base extracted from records of soldiers recruited to the British Army from 1760 to 1870. A great deal of work was expended on the collection and analysis of the registers. However, according to the analysis in the following pages, the yearly averages of statures at recruitment dates are strongly affected by decisions by the military authorities, and cannot be used to reconstruct the conditions at birth date.

The general intentions in using large data sources on soldiers’ heights, are to demonstrate the movements during a period, and investigate if the short periods of low stature correspond to times of hardship at the birth date, and if the long-term figures of heights show an increase or a decrease. The main data base used by the academics, is that of Floud, Wachter and Gregory, taken from the «description books»of soldiers enlisted in the British Army from 1760 to 1870.

The process was a) collect the soldiers by year of enlistment, b) correct the set of heights for truncation, caused by the minimum height standards, c) regress the data per soldier to his birth year, as we suppose that the factors that cause the differences in stature, come from the first years of life, d) calculate the average height of the men for each year of birth.

It is not possible to understand from the exposition in the 1990 book, how the basic recruitment data were transformed into the final numbers presented by the researchers:

- the original real-world data, e.g. the average heights of the recruits per year and per age in the description books, were not exhibited; only the «processed» data after the correction for truncation, and assignation to the birth-year;

- the average heights (after correction for truncation) were not exhibited per year, only per quinquennium or per decade;

- the arithmetical process for truncation was not illustrated in examples;

- there was no informations as to the differential effect of the correction, e.g. how much was the decrement in height, and how many figures of decades did not require the correction;

- it was supposed that all the movements in the average heights were caused by the wages, food consumption, and sanitation and housing conditions in the childhood years of each recruit, and not by military decisions at the recruitment date;

- it was supposed that the only necessary correction was that of compensation for the Minimum Height Standard, and not for peace/war conditions, urgency of recruitment, number of recruits required in the year, or bounty payments.

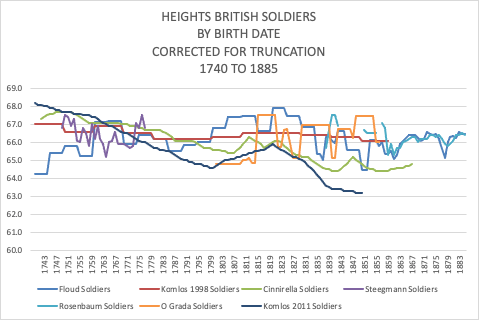

Unsurprisingly the academic investigations have not given consistent results:

SSTs

| Floud Roderick Floud, Kenneth Wachter, Annabel Gregory; Height, Health and History, Nutritional Status in the United Kingdom, 1750-1980; 1990; Table 4.1, Mean heights of military recruits by age and date of birth, pp. 140-149 (includes Army and Royal Marines) (averages per quinquennium up to 1855) Here: age 22 |

| Komlos 1998 John Komlos; Shrinking in a Growing Economy?, The Mystery of Physical Stature during the Industrial Revolution The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 58, No. 3(Sep. 1998), pp. 779-802; www.jstor.org/stable/2566624 Figure 2, Height of English Soldiers, 20-23 year olds, p. 781. |

| Cinnirella Francesco Cinnirella; Optimists or Pessimists?, a Reconsideration of Nutritional Status in Britain, 1740-1865; European Review of Economic History, December 2008 Figure 7, Average Height Trend in Britain, 1740-1865, p. 339, 18 year olds |

| Steegmann Theodore Steegmann; 18th Century Military Stature: Growth Cessation, Selective Recruiting, Secular Trends, Nutrition at Birth, Cold and Occupation; Human Biology, Vol. 57, No. 1, pp. 77-95 www.jstor.org/stable/41463634 Fig. 2, Mean stature for a cohort of mature men, according to year of birth, English and Irish soldiers of 21 years or older |

| Rosenbaum S. Rosenbaum and J. P. Crowdy; 100 Years of Heights and Weights, Journal of Research, Army Medical Corps, June 1992; www.jstor.org/stable/2982758 Table 1, Heights of Recruits (inches) 1860-1974, Age 20-24 |

| Ó Grada Cormac Ó Grada and Joel Mokyr; Height and Health in the United Kingdom: Evidence from the East India Company Army, Working Papers 199407, School of Economics, University College Dublin, 1994 |

| Komlos 2011 John Komlos and Helmut Küchenhoff; The Diminution of the Physical Stature of the English Male Population in the eighteenth Century; Cliometrica, 2012, 6; pp. 45-62 Fig. 5, Four estimates of the Height of Englishmen by Year of Birth, p. 54 (Average of Army and Royal Marines) |

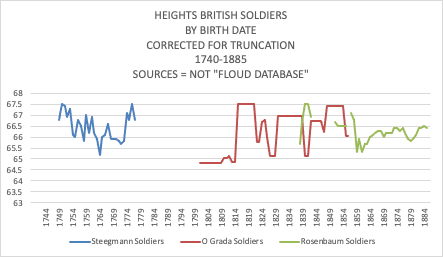

The “Floud”, “Komlos 1998”, “Cinderella”, and “Komlos 2011” lines all use the “Floud database”; the second and last reports come from the same investigator.

So we have to inspect the original data in the “Floud Database”.

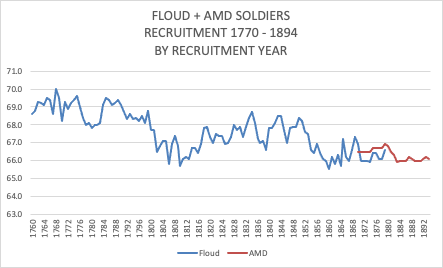

To attempt to understand how the four different graphs were formed out of the “Floud data”, it is necessary to present the original numbers from the collection of the “description books”. The following graph shows the totality of the registers referring to: British Army, not Irish born, not less than 18 years old. Total yearly numbers from the Army Medical Department reports for 1870 to 1894 are added.

We note average heights from 68 to 70 inches, for the period 1760 to 1799. They are doubtful for the following reasons:

- a decrement of 2 inches in 40 years is considerable;

- a fall of 2 inches from 1799 to 1802, in the heights of the men being enlisted, is not explicable, unless the laws had changed;

- the heights given for the Royal Marines in the Floud data in this period, do not show this extreme movement;

- there is no contemporary report, that the soldiers were extremely tall;

- an investigation of heights of British-born soldiers in the War of American Independence (Komlos), gives 65.5 inches;

- this is not congruent with the minimum height requirement of 64 inches from 1779;

- male convicts had an average height of 66 inches in this period;

- the only contemporary report of heights of a non-army group (Dorset Militia 1798/99) shows 66.5 inches.

Some academics consider that this large difference between “before 1800” and “after 1800”, demonstrates that the English population had sufficient food in the eighteenth century, but insufficient food in the first half of the nineteenth century.

The explanation appears to lie in the selection of the “description books” by Floud’s team.

The “description books” were bound pages, used by the administration of the British Army from 1760 to 1890, containing information – one page per soldier – with physical characteristics including the height at the date of enlistment. The books were the property of each regiment. They are now findable in the National Archives [although many are missing, or were never formulated]. For each decade, Floud’s team took the regiments that had description books for that decade, and took randomly one or some of the books, to transcribe the description to a computer system.

But in the National Archives, for the period 1760 to 1799, the only regiments with description books are those that are part of the Royal Artillery (revised in the “Search” function of the National Archives system, and kindly confirmed by the staff of the National Archives). So Floud’s team used only those description books (in Floud’s datafiles for those years, the column for the identification of the regiment has the value of “WO54”, which is the value in the organization of the National Archives for “Royal Artillery”).

But the root of the problem is that the soldiers in the Royal Artillery were “big guys”. Their job was to dismantle and rebuild the field guns, to transport them over difficult terrain, often without the help of horses, and to insert the shells into the mouth of the cannon. In the nineteenth century, their minimum height was 4 inches above that of the infantry, and the chest minimum was 2 inches above that of the infantry. “No minimum chest measurement was specified before 1860, when a minimum of 33 in. was given except in the case of the recruits for the Artillery whose minimum was fixed as high as 35 in. because the heavy work involved in manhandling pieces of ordnance was considered to require a greater vital capacity” (Lt. Col. Derek Levis, Royal Army Medical Corps, “The Progress in Public Health ….”, 1949, p. 133). “Ordnance Department: Recruits for this branch of the service ought to be powerful athletic men. The duties of the field, and even of the arsenal, are laborious and require great strength.” (Henry Marshall, Deputy Inspector-General of Army Hospitals, On the Enlisting …., 1840, pp. 52-53).

So we may assume that this is the reason that the data from 1760 to 1799 give much higher statures than for the following years.

How much was the difference? For the decades 1800’s and 1840’s, the Floud data files give the regiment key and the height in each case. In the 1800’s decade, the Artillery soldiers had an average height of 67.7 inches, and the non-Artillery had an average height of 66.1 inches. In the 1840’s decade, the Artillery soldiers had an average height of 69.1 inches, and the non-Artillery 67.5 inches. Thus we may suppose a difference of 1.5 inches.

So we recalculate the heights in the datafiles of 1760-1769, 1770-1779, 1780-1789, and 1790-1799, subtracting 1.5 inches from every position. For the datafile of 1800-1809, which has a mixture of Artillery and non-Artillery, we subtract 1.5 inches from only the Artillery positions.

This is the result:

REQUIRE TO EXPLAIN THE CONCEPT OF «TRUNCATION»

REQUIRE TO EXPLAIN THE ADJUSTMENT PROCEDURE

aaaa

We wish to use this information to have the best possible idea of what was the average height of that segment of the population, which decided to enlist as a soldier (or would have decided, if they had complied with the minimum height regulation). The clearest information is that of war years with large requirements for personnel, or with urgent needs for personnel, as in those circumstances the military authorities did not apply the minimum height regulations, and thus the men who were enlisted mirrored the distribution of heights in the totality of the working-class part of the population. Actually, we know that 20 % of the Army in the period 1800-1815 was under the minimum height.

From the graph above, we have the values of 66.0 inches in 1777-1782 (War of American Independence), 66.0 inches in 1791-1812 (Napoleonic Wars), 66.6 inches in 1837-1838 (Revolts in Upper Canada and in Lower Canada), and 66.0 inches in 1858 (end of the Crimean War plus the “Indian Mutiny”. We can suppose that the average in this segment of the population was 66 inches, continuously from 1776 to 1860. Note that this segment of the population was of those persons of the lower working class, who had some individual personal problem, which practically obliged them to join the Army.

The average statures in the period 1760-1775 were high, at 67 to 68 inches, as the minimum height requirement was 66.5 inches.

The period of the Revolts in Upper Canada and in Lower Canada in 1837-1838 illustrates the decrease in average heights of new recruits, when the military authorities urgently needed to increase the numbers of the military forces.

| Year | Recruits (*) | Av. Height (**) | |

| 1834 | 3,700 | 68.7 | |

| 1835 | 6,600 | 68.1 | |

| 1836 | 6,900 | 67.2 | |

| 1837 | 13,300 | 67.0 | |

| 1838 | 22,000 | 67.1 | |

| 1839 | 16,900 | 66.6 | |

| 1840 | 14,800 | 67.8 | |

| 1841 | 16,600 | 67.8 | |

| 1842 | 13,000 | 68.1 |

ttt

(*) not including Artillery

(**) without correction for truncation

The statures in the 1840’s were high, because the authorities decided to recruit only a small number of soldiers, as they did not expect any wars. We know this, because they were taken by surprise by the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1853. There were nominally 70,000 soldiers in Britain, but this included soldiers in movement to and from overseas posting, infirm men, and untrained new recruits. It was with difficulty that 25,000 soldiers were found, who could be transported for action in the Black Sea area. Foreigners were found to fight as mercenaries, in the British German Legion, the British Italian Legion, and the British Swiss Legion (these were 14,000 men in total, but they did not actually engage in the hostilities). It was calculated at the beginning of the War, that 40,000 new recruits would be required. For this reason, the minimum height limits were disregarded, and the average heights of the new recruits decreased rapidly. The War ended in 1856.

This was then followed by the “Indian Mutiny” in 1857-59. This required a further increase in the “Establishment” (authorized total number of soldiers) of the Army. Thus the average heights of new recruits decreased further to 66 inches in 1859.

By an application of «Occam’s Razor», we see that it is not necessary to suppose that the heights of the men at their enlistment, was a function of the living conditions in their first few years of life.

Our first source is of the Dorset Militia Ballot List of 1798-99 (Jaadla et al., 2020). The Militia Ballot Lists collected the names, ages, heights, and family status of all adult males in each county. If the domestic Militia was made active – against a real risk of invasion from France – a ballot would be carried out to decide those men who would be enlisted.

The evidence that has survived in the case of Dorset, gives us all adult males 18 – 45 in half of the parishes. We have 6753 useful observations from 227 parishes; the total population of the county was about 95,000. The men who appear in the list are 3.0 % elite, 4.9 % lower middle class (clerks, merchants, dealers), 38.5 % skilled workers (makers, smiths, weavers), 8.8 % farmers and yeomen, 44.8 % unskilled workers (agricultural and general labourers).

The average height was 66.4 inches (168.7 cm.). The farmers were about 0.8 inch taller than the labourers. There is no reason to doubt that this sample is representative of the whole of England at that time.

(Jaadla, Hannaliis; Shaw-Taylor, Leigh; Davenport, Romola; Height and Health in late eighteenth-century England; Population Studies, A Journal of Demography, published online 29th September 2020)

| Height | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 72 | Total | ||

| Per cent | 1.2 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 8.2 | 13.1 | 24.2 | 18.6 | 15.6 | 7.5 | 5.5 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 100.0 |

(The “inch column” for e.g. “64” shows the numbers of 63.5 inches to 64.5 inches)

AVERAGE HEIGHT 66.4 INS. (168.7 CMS.)

We now have some “innocent remarks”, which show that the “normal height” of men outside the manufacturing towns was 5 ft. 7 ins. to 5 ft. 8 ins.

“A recruiting officer testified that operatives were little adapted for military service, looked thin and nervous, and were frequently rejected by the surgeons. In Manchester he could hardly get men of 5 ft. 8 in.; they were usually only 5 ft. 6 in. to 7 in., whereas as in the agricultural districts, most of the recruits were 5 ft. 8 in.”

(Wing, Evils of the Factory System, 1837, p. cii; quoting the First Report of the Factories Inquiry Commission, 1833, Mr. Tufnell’s Evidence, p. 59)

“Their stature low – the average height of four hundred men, measured at different times, and at different places, being five feet six inches.”

(Gaskell, The Manufacturing Population of England, 1833, pp. 161-162)

Serjeant Buchan – Recruiting Serjeant: “The general height of men in this town [Birmingham] is 5 ft. 4 in. to 5 ft. 5 in. …. They are generally shorter than in any town he has known. … The countrymen from the neighbouring districts, are generally taller and stouter.”

(Children’s Employment Commission, Appendix to the Second Report of the Commissioners: Trades and Manufactures, 1843, part 1, p. f 170, interview 495)

In 1844, a Dr. John Hutchinson, who wished to test his new invention, a spirometer (for measuring the strength of the lungs), invited a number of people from different walks of life, to use the object. He registered their height and weight, as well as the measurement of the expulsion of the lungs.

(John Hutchinson, Surgeon, Lecture on Vital Statistics, The Lancet, Vol. 1, No. 19, June 1844, pp. 567-570)

The data as to heights were as follows:

| Classes | less 5 0 | 5 0 | 5 1 | 5 2 | 5 3 | 5 4 | 5 5 | 5 6 | 5 7 | 5 8 | 5 9 | 5 10 | 5 11 | 6 0 more |

| Seamen | 5 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 10 | 9 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 11 | 18 | 12 | 6 | 2 |

| Fire Brigade | 1 | 2 | 20 | 17 | 26 | 20 | 3 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Metropolitan Police | 4 | 33 | 46 | 22 | 13 | 12 | 11 | |||||||

| Thames Police | 1 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 15 | 17 | 10 | 5 | 3 | |||||

| Paupers | 7 | 3 | 10 | 10 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 9 | |

| Mixed Class | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 17 | 16 | 20 | 20 | 28 | 16 | 14 | 7 | 9 | 14 |

| Grenadier Guards | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 22 | 16 | 11 | 1 | ||||||

| Compositors | 3 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 3 | |||||

| Pressmen | 1 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 2 | ||||||

| Draymen | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 4 | |||||||

| Gentlemen | 1 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 14 | 10 | 18 | 16 | 8 | 12 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Pugilists, &c. | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | |||

| Horse Guards (Blue) | 30 | 26 | ||||||||||||

| Total | 14 | 6 | 27 | 22 | 68 | 78 | 118 | 102 | 172 | 164 | 98 | 75 | 82 | 62 |

Average without Horse Guards, 5 ft. 7.3 in., average without Horse Guards, Metropolitan Police, Grenadier Guards, Gentlemen, 5 ft. 6.7 in.

Skeletons

The most objective evidence for the heights in the past, is that of skeletons, as they do not change in length, and are perfectly measurable (more exactly, the length of the femur is taken, and converted by a formula to the height of the person while alive).

We have a number of results from different Burial Grounds in England, from the second half of the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth century.

The average stature for men from each case, ranges between 5 ft. 6 ½ in. to 5 ft. 7 ½ in. (leaving out two higher values from the “upper middle class” and “upper class”); for the women it is from 5 ft. 1 ½ in. to 5 ft. 3 in.

| Church | Place | Period | Context | Social class | Adults number | Males height ins. | Males height cms. | Females height ins. | Females height cms. |

| N | Lancashire | 19th Century | Urban | N | 311 | 66.4 | 168.7 | 62.2 | 158 |

(Excavation 2020-2021, Personal communication)

| Church | Place | Period | Context | Social class | Adults number | Males height ins. | Males height cms. | Females height ins. | Females height cms. |

| Quaker Church, Coach Lane | N. Shields | 1711-1857 | Urban | Low and Middle | 154 | 66.5 | 169 | 61.8 | 157 |

| St. Hilda, Coronation St. | S. Shields | 1816-1855 | Urban | Working Class | 114 | 67.7 | 172 | 62.3 | 159 |

| Chelsea Old Church | London | 1712-1842 | Sub-urban | Higher Class | 165 | 66.1 | 168 | 64.2 | 163 |

| St. Benet Sherehog | City of London | <1853 | Urban | Middle Class | 166 | 66.9 | 170 | 63.0 | 160 |

| Bow Baptist | Outskirts London | 1816-1856 | Sub-Urban | Middle Class | 214 | 66.9 | 170 | 62.2 | 158 |

| Cross Bones | Southwark | 1800-1853 | Urban | Pauper | 44 | 66.7 | 169 | 63.0 | 160 |

(Newman, Sophie Louise; The Growth of a Nation: Child Development in the Industrial Revolution in England, c. AD 1750-1850; Doctoral Thesis, Durham University, 2016; Figure 6.4., p. 246)

| Church | Place | Period | Context | Social class | Adults Number | Males height ins. | Males height cms. | Females height ins. | Females height cms. |

| St. Bride’s, Lower Cemetery | Farringdon Street London | 1770-1849 | Urban | Workhouse and Prison | 125 | 66.5 | 169 | 63.2 | 160.5 |

| St. Pancras Old Church | Camden London | 1793-1854 | Urban | Outside Metropolis, Immigrants Refugees | 448 | 67.3 | 171 | 61.8 | 157 |

| St. Mary-le-bone | West- minster | 1773-1850 | Urban | High Status | 138 | 66.9 | 170 | 62.6 | 159 |

Museum of London > Wellcome Osteological Database > Post-Medieval Cemeteries

| Church | Place | Period | Context | Social class | Adults Number | Males height ins. | Males height cms. | Females height ins. | Females height cms. |

| St. Peter-le-Bailey, Bonn Square | Oxford | 1726-1855 | County town | Poor and paupers | 120 | 67.7 | 172 | 62.2 | 158 |

| St. Luke’s | Islington | 1760-1850 | Suburb London | Upper working class | 533 | 66.9 | 170 | 62.2 | 158 |

| Infirmary | Newcastle | 1745-1845 | County town | Poor working class | N | 67.3 | 171 | 63.0 | 160 |

| St. Bartholo- mew’s | Penn, nr. Wolver-hampton | 1664-1818 | Country town | Upper middle class | 202 | 68.9 | 175 | 63.0 | 160 |

| St. Nicholas | Sevenoaks | 1550-1875 | Country town | Middle class | 116 | 68.1 | 173 | 63.4 | 161 |

| St. George’s (crypt) | Bloomsbury | 1800-1856 | Inner London | Upper middle class | 111 | 67.7 | 172 | 63.0 | 160 |

| Christ Church | Spitalfields | 1729-1852 | Inner London | Masters, weavers, traders | 623 | 66.5 | 169 | 61.4 | 156 |

| Quaker Burial Ground, London Road | Kingston-upon-Thames | 1664-1818 | Country town | Quakers | 295 | 66.5 | 169 | 63.0 | 160 |

(Helen Webb and Andrew Norton, The Medieval and Post-medieval Graveyard of St. Peter-le-Bailey, at Bonn Square, Oxford, Oxoniensia 2009, Oxford Architectural and Historical Society, pp. 137 et seq., Excavation in 2008.

Angela Boyle, Ceridwen Boston, and Annsofie Witken, The Archaeological Experience at St. Luke’s Church, Old Street, Islington, Oxford Archaeology, 2005, Table 5.21.

Other sites taken from this above source, Table 5.21 and pp. 205-7)

John Beddoe was a Fellow of the Royal Society, and President of the Royal Anthropological Institute from 1889 to 1891.

In 1870 carried out a survey of the whole of the United Kingdom, through a system of written questionnaires, which he sent out to a large number of academic contacts and administrative persons in the country. The responses that he reports in his book, refer to all classes of persons, except the rich and the professions, and the destitute and unemployed, and to many types of occupation. But exclusively men! In general from 25 to 49 years old. The total of men documented in the book was 8,583. The number with complete data was 3,498.

They are presented as one line for each reply from a «coordinator» about a group of persons, for example «agricultural labourers in the neighborhood of Hull». Each line may refer to from 10 to 100 men. Returns for «recruits», «lunatics», and «convicts» are given in separate sections.

| Under 5 ft. 6 in. | 5 ft. 6 in. to 5 ft. 7 in. | 5 ft. 7 in. to 5 ft. 8 in. | 5 ft. 8 in. to 5 ft. 9 in. | Above 5 ft. 9 in. | Average | |

| Normal | 14 | 76 | 82 | 47 | 20 | 5 ft. 7.4 in. |

| Criminals | 19 | 10 | 1 | 5 ft. 5.7 in. | ||

| Recruits | 10 | 13 | 5 ft. 7.0 in. | |||

Compilation of data, per report line (here: only England), made by this author.

Some years ago, James Riley was able to access (in the University of Bristol), the original reports which had been received by Dr. Beddoe.

He was able to carry out analyses of the data in different dimensions. The distribution by occupations was as below, showing a larger proportion of working class than in other contemporary estimates (this would mean that Beddoe’s value of the average might have been a little low). We note that the workers in manufacturing are the shortest.

Mr. Riley’s calculation – using Dr. Beddoe’s sample – of the average height in the population of England and Wales in 1870 was 66.9 inches (169.9 cm.).

He also plotted the heights against the ages:

We see that the height practically does not change with age. But we are processing men with an age of 23 to 50 years, in which period the height of the man does not change. This then means that the average of the final heights of men through the period 1841 to 1866 (born 1817 to 1841) did not change.

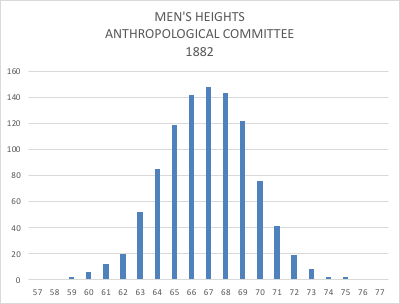

Report of the Anthropomorphic Committee of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (1879 and 1883)

This was a collection of data from a) the Beddoe survey, b) the investigation of Dr. Roberts about Factory Children (1876), and an own survey. In total, these were about 53,000 individuals of all classes, all ages (including children), and both sexes. The total of adult males of the United Kingdom was 8,585, and the adult males in England only was 6,194.

| Heights | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 75 | |

| Per mille | 1 | 2 | 6 | 12 | 20 | 52 | 85 | 119 | 142 | 148 | 143 | 122 | 76 | 41 | 19 | 8 | 2 | 2 |

AVERAGE HEIGHT = 67.4 INCHES (171.2 CMS.)

There is a table in the report which show the heights of the men in the report, detailed according to the age of the men in approx. 1880. This allows us to say, for example, that the men of age 29, who were born in 1851 and were 20 years old in 1871, had an average height of 67.9 inches in 1871. Thus we may take it as a reasonable assumption, that referring to all the men of 20 years old, who were alive in the country in 1871, they had an average height of 67.9 inches. 20 years was the age at which the men attained their maximum height, which generally they maintained until 60 years old.

So we can suppose that the average height of men of from 20 to 60 years old, was from 67.5 to 68.0 inches in the period 1840 to 1880.

| Age 1880 | 20th Birthyear | Height inches | |

| 20 | 1880 | 67.5 | |

| 21 | 1879 | 67.6 | |

| 22 | 1878 | 67.7 | |

| 23 | 1877 | 67.5 | |

| 24 | 1876 | 67.7 | |

| 25 | 1875 | 67.7 | |

| 26 | 1874 | 67.8 | |

| 27 | 1873 | 67.9 | |

| 28 | 1872 | 67.7 | |

| 29 | 1871 | 67.9 | |

| 30-35 | 1865-1870 | 68.1 | |

| 35-40 | 1860-1865 | 68.0 | |

| 40-50 | 1850-1860 | 68.0 | |

| 50-60 | 1840-1850 | 67.9 |

Table XVI, p. 290, and Table XX, p. 294

There was a considerable differentiation in heights in the different counties of the British Isles:

Anthropomorphic Committee 1882, Map no. 1, Plate I.

We return to the point at the beginning of this document, that the high value for the men’s stature in our days, is due to the increases since the end of the Second World War; these were caused by considerable improvements in medicine and health care (National Health Service), monetary income, and food consumption. The average height of men in the general population was a little more than 5 ft. 7 in. This means that the average height of men in the nineteenth century was the same as that of the men who fought in the Second World War. See the following studies:

W. F. F. Kemsley, “Weight and Height of a Population in 1943”, Annals of Human Genetics, 1950, 27,000 men and 33,000 women; men 20-24 67.0 in. (170.1 cm.); women 20-24 62.4 in. (158.5 cm.)

E. M. B. Clemens and Kathleen Pickett, “Stature and Weight of Men from England and Wales in 1941”, British Journal of Preventive and Social Medicine, 1957, study of 21,300 men measured by medical boards in 1941, previous to call-up; height of men in England 67.1 in. (170.4 cm.)

W. J. Martin “The Physique of Young Adult Males”, Medical Research Council, Memorandum No. 20, H. M. S. O. 1949, report of 91,000 men intended for Air Force 1939; 67.3 in. (170.9 cm.)

The report of the Anthropometric Committee also tells us the average height is clearly affected by the type of occupation, particularly that the factory workers were about 1 ½ inches shorter than the generality of the population.

| Average height, inches, 25-30 years | ||

| Total Population | 67.4 | |

| Class I | Professional Classes | 69.1 |

| Class II | Commercial Classes, Clerks and Shopkeepers | 67.9 |

| Class III | Labouring Classes: Agricultural, Miners, Sailors, Shopkeepers | 67.5 |

| Class IV | Artisanal Classes, living in Towns | 66.6 |

| Class V | Sedentary Occupations: Factory Operatives, Tailors | 65.9 |

This was generally commented at the time (together with the statement that town dwellers were shorter than rural inhabitants), for example:

“I have been informed that of those labourers now employed in the most important manufactories, whether natives or migrants to that town, the sons who are employed at the same work are generally inferior in stature to their parents.”

(Edwin Chadwick, Inquiry into the Sanitary Condition…., 1842, p. 185)

The working people in Manchester (not just the cotton workers) were well known to have a “shrunken” appearance, but this did not mean that they were physically weak.

“Of course the air in which they work exercises a marked effect upon the appearance of the people. This is a subject which I shall treat of at length later; but I may be here permitted to remark upon the more obvious physical characteristics of carders, spinners and weavers. In the first place I do not remember seeing one male or female adult to whom I would apply the epithet of a “stout “ man or woman. There is certainly no superfluity of flesh in the factories. When I say this I do not by any means intend to insinuate that the people are unhealthy or unnaturally lean; they are generally thin and spare but not emaciated. By such occupation as is afforded in the various branches of cotton spinning, much muscle cannot be expected to be developed. There is no demand for it – the toil does not require it – it would be useless if it existed. I cannot therefore term the appearance of the people “robust”. They present no indication of what is called “rude” health. They are spare, and generally – so far as I can judge – rather undersized. At the same time their appearance cannot rightly be called sickly. Their movements are quick and easy, with nothing at all of langour expressed either in face or limbs. The hue of the skin is the least favourable characteristic. It is a tallowy-yellow. The faces which surround you in a factory are, for the most part lively in character, but cadaverous and overspread by a sort of unpleasant greasy pallor. Now and then you observe a girl with some indications of roses in her cheeks, but these cases are clearly the exception to the rule; and amid the older and matronly women not a single exceptional case of the kind did I find. Altogether, the conclusion which a very careful examination of the people led me to was this, that the labour cannot be said to exercise a seriously stunting or withering effect upon those subjected to it – that it does, perhaps, make them actually ill, but that it does prevent the full development of form, and that it does keep under the highest development of health. Men and women appeared to be more or less in a negative sanitary condition. At any rate what is called the “bloom of health” is a flower requiring more air and sunshine than stirs and gleams athwart the rattling spindle.”

(Ginswick, Jules, Labour and the Poor in England and Wales 1849-1851, Letters to the Morning Chronicle from Correspondents, Vol. 1, Lancashire, Cheshire, Yorkshire, pp. 15-16, The Physical Appearance of the Factory Workers)

“It is perfectly true that the Manchester people have a sickly, pallid appearance; but this is certainly not attributable to factory labour, for two reasons: first, because those who do not work in factories are equally are equally pallid and unhealthy-looking, and the sick society returns show that the physical condition of the latter is not inferior:- secondly, because the health of those engaged in country cotton factories, which generally work longer than town ones, is not injured even in appearance … Mr. Wolstenholme, surgeon at Bolton, says that “the health of factory people is much better than their pallid appearance would indicate to any person not intimately with them.””

(Factories Inquiry Commission, Supplementary Report … as to the Employment of Children in Factories, 1834, Part I, Mr. Tufnell’s Report from Lancashire, p. 198)

The question is, how did it happen that the factory workers were shorter (but not to the degree of “stunted”) than the average of the population?

It was not due to insufficient food, because we know that the people in the Northern industrial towns ate a considerable amount of meat. It was not due to excesses in the physical human work required, because – at least from 1830 onwards – the work of pushing, cutting, winding, pulling, etc. was done by the machines, and the human being only had to supervise the work of the machines. It may have been partially due to the sanitary and epidemic problems in the towns.

The main reason was probably the low amount of physical bodily work required in the factories. As it says in the table above: “sedentary”. “The work appeared to us, like most of the labour in a cotton mill, to require very little muscular effort beyond that of standing and walking.» (Bridges and Holmes, 1873, p. 15)

a

Curiously, if the work in the factories had been at a level that the human frame had been used to for the previous 500 years, the average height of the manufacturing workers would have been more, and the male population might have been about ½ inch taller.

Women

The data from above referring to skeletons, give averages per burial ground of from 61.4 to 63.2 inches.

The Anthropometric Committee Report of 1883 gives an average height for women of 62.6 inches, but this is based on only 379 observations.

There was practically no movement in heights until the end of the Second World War. The average height of women in 1943 was 62.4 inches; see Kemsley (1950) above.

Children

We do have more surveys (actual measurement) of the heights of children during the nineteenth century. This is due to the fact that these data were required for the preparation of laws for the protection of the children, or as a basis for permission for individual boys or girls to work, as the laws proscribed the number of hours that could be worked, in terms of the age of the children.

| As we noted at the beginning of this document, the World Health Organization definition of “stunting” is “height more than two standard deviations below the average height for the general population, at the given age”. This would be about three inches below the average in the case of children. The only children or young persons with employment below this level in the nineteenth century, were the nail- and chainmakers in the Black Country. There certainly were very poor children who lived on the streets, who were about this level. There were poor boys in London, who ate very badly, and many were covered in rags, and were cared for by the Maritime Society, to be enrolled in Royal Navy ships. In 1800 they had heights of 51 inches at age 13 (Floud, Wachter, 1982, p. 435). From about 1835, Industrial Schools were founded, which gave bed and food for children collected from the streets, and gave them school education and technical education. The average height of boys in the Industrial Schools in 1882 at 14 years, was 7 inches less than boys of the general population, and 24 lbs. less in weight (Anthropometric Commission, 1882-83, Table XXI, p. 296). |

The first examination of heights of boys and girls was in 1833 in Manchester and Stockton, to check if the children in the cotton factories were particularly shorter than the children in other occupations. In the course of the first attempt to formulate a law for the protection of the children, in 1819, many doctors and professional persons in Lancashire had given evidence that the children were exceedingly overworked, that they were short and weak, that you could recognize a “factory child” at a distance by the stature of his/her body.

To the surprise of later investigators in 1833, the factory children were of exactly the same height as the non-factory children. It appears that the machinery had changed, such that there was less heavy work, and less distance to be walked per day in the workplace. Also the non-factory children would probably not be well fed, as many of them were the sons and daughters of domestic hand-loom weavers, who were at a very low level of incomes.

In any case, the average height of 4 feet for the 9-year olds is very low in our terms of today. The 9-year olds are 48 / 66 = 73 %, and the 11-year olds are 51 / 66 = 77 %, of the height of the father. The 9-year olds are of deficient weight, 51 lbs. against the 61 lbs. of the 11-year olds.

Leonard Ward, “The Effect, as shown by Statistics, of British Statutory Regulations directed to the Improvement of the Hygienic Conditions of Industrial Occupations”, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Vol. 68, No. 3 (Sep. 1903), pp. 435-525, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2339590

(Numbers rearranged by Mr. Ward)

Page 461

Mr. Leonard Horner was named Factory Inspector in the District of Lancashire, Cheshire, and Yorkshire in 1836. He did not like what he saw in the factories, as it appeared that the children were too small for the ages at which they were authorized to work. “In going through the factories in different parts of my district I was particularly struck with the diminutive size of many children who were working 12 hours, and, on calling for their certificates I found children certified to have the “ordinary strength and appearance” of 13 years of age who were manifestly to the most common observation, not more than 10 or 11. It was evident that has been either the most culpable negligence on the part of the surgeons, or that fraud had been very extensively practiced upon them under a false name, in order to obtain a certificate which was to be made use of by a younger child.” (Circular Letter to Surgeons, 20thSeptember 1836). What was happening, was that the parents wanted/needed the income from the child, who legally could not work under those circumstances, and so they gave false information.

Mr. Horner decided that he needed assured evidence as to the general range of heights for each age, so as to be able to define limits in terms of the height. He sent a circular letter to a number of doctors in his district, requiring them to collect a number of children in the mills, of whom there was no doubt as to their ages, and to report their heights. There were 72 doctors, who measured and reported on 16,400 boys and girls, in factory employment.

The results were as follows:

| Years of Age | Number Males | Average Height | Number females | Average height | ||

| Ft. in. | Ft. in. | |||||

| From 8 and under 9 | 666 | 3 10.2 | 539 | 3 9.5 | ||

| From 9 and under 10 | 945 | 3 11.6 | 813 | 3 11.8 | ||

| From 10 and under 11 | 1124 | 4 1.3 | 927 | 4 1.2 | ||

| From 11 and under 12 | 1223 | 4 2.8 | 1055 | 4 2.7 | ||

| From 12 and under 13 | 1427 | 4 3.7 | 1330 | 4 4.1 | ||

| From 13 and under 14 | 2133 | 4 5.7 | 2240 | 4 5.8 | ||

| From 14 and under 15 | 117 | 4 8.2 | 140 | 4 9.0 | ||

| From 15 and under 16 | 82 | 4 10.5 | 106 | 4 10.7 | ||

| From 16 and under 17 | 43 | 5 0.5 | 90 | 4 11.5 | ||

| From 17 and under 18 | 47 | 5 0.0 | 112 | 5 0.0 |

(The age data were given in the publication, in divisions of half-years; the heights were given to the nearest eighth-inch)

Charles Knight (ed.), “Practical Application of Physiological Facts”, The Penny Magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, Volume 6, 1837, pp. 270-272.

The heights in the two cases are very similar. But they do seem low to us at the present time. The question is: are these low statures a) those that had existed for (e.g.) the previous 50 years, or b) are they lower than they had been previously, due to the introduction to factory work?

We can compare these figures with those of the Belgian scientist, M. Quetelet, which he collected in Belgium in 1832 (see “A Treatise on Man and the Development ofhis Faculties”, English edition, 1835, p. 64). An inspection of the information as to Belgium gives: boy of 9 years 122.7 cm. (48.3 in.), boy of 11 years 132.7 cm. (52.2 in.), girl of 9 years 122.0 cm. (48.0 in.), girl of 11 years 127.5 (50.2 in.). The weights are: 24.1 kg. (53.1 lb.). 27.8 kg. (61.4 lb.), 22.4 kg. (49.5 lb.), 26.2 kg. (57.9 lb.). These figures – which are for the general child population of Belgium – are very close to those in the factories of the North of England. And Belgium at this time had very few factories. So we may suppose that these heights and weights were “normal” for the time.

The average height of men in Belgium was, according to M. Quetelet, at 30 years old, 168.4 cm. (66.3 in.), and of the women was 157.9 cm. (62.2 in.).

Dr. Bridges and Mr. Holmes were requested by the Local Government Board in 1873, to inspect the textile factories in all England, to give an opinion, if the hours of work should be reduced, and the ages of children authorized to work should be increased.

About 10,000 children were measured, and the results were as follows:

Table A: Factory Children of Factory Parents (Urban and Suburban)

| Age | Boys | Girls | ||||

| No. | Inches | No. | Inches | |||

| 8 | 30 | 45.7 | 30 | 46.5 | ||

| 9 | 80 | 48.0 | 110 | 47.6 | ||

| 10 | 140 | 49.8 | 130 | 49.5 | ||

| 11 | 130 | 51.4 | 120 | 50.8 | ||

| 12 | 120 | 52.8 | 140 | 53.1 |

Table B: Children in Non-factory Districts (Urban and Rural)

| Age | Boys | Girls | ||||

| No. | Inches | No. | Inches | |||

| 8 | 140 | 46.7 | 100 | 46.7 | ||

| 9 | 230 | 49.2 | 160 | 48.6 | ||

| 10 | 240 | 51.0 | 140 | 50.1 | ||

| 11 | 180 | 52.9 | 140 | 52.7 | ||

| 12 | 150 | 54.0 | 90 | 54.4 |

Table C: Non-factory Children of Non-factory Parents in Factory Districts (Urban and Suburban)

| Age | Boys | Girls | ||||

| No. | Inches | No. | Inches | |||

| 8 | 20 | 46.7 | 20 | 47.4 | ||

| 9 | 60 | 49.1 | 30 | 49.4 | ||

| 10 | 50 | 51.0 | 30 | 49.8 | ||

| 11 | 30 | 52.6 | 30 | 52.8 | ||

| 12 | 20 | 53.6 | 17 | 53.4 |

Table D: Urban Factory Children (Irrespective of Parentage)

| Age | Boys | Girls | ||||

| No. | Inches | No. | Inches | |||

| 8 | 109 | 46.8 | 89 | 46.5 | ||

| 9 | 235 | 48.3 | 269 | 47.9 | ||

| 10 | 361 | 49.6 | 314 | 50.0 | ||

| 11 | 284 | 51.4 | 292 | 51.6 | ||

| 12 | 316 | 52.6 | 312 | 52.7 |

Table E: Suburban Factory Children (Irrespective of Parentage)

| Age | Boys | Girls | ||||

| No. | Inches | No. | Inches | |||

| 8 | 131 | 47.1 | 95 | 46.3 | ||

| 9 | 279 | 48.3 | 216 | 48.1 | ||

| 10 | 282 | 50.4 | 279 | 49.8 | ||

| 11 | 302 | 51.8 | 275 | 51.7 | ||

| 12 | 264 | 53.2 | 266 | 53.3 |

As is to be expected, the non-factory children are taller than the factory children.

“He was perfectly satisfied from close observation during the last ten years, in a situation which gave him the best opportunities of judging, that the children of the mill population were steadily, year by year, getting smaller and physically less capable of doing their work. If they asked him how that was he would tell them. In the first place, it was owing to a great extent to the intemperate habits of the parents transmitting feeble constitutions to the children; and in the next, to the mistaken manner in which the mill people feed their children. They brought them up on tea and coffee, instead of upon more substantial food. As an example: During the last month in the Great Bolton district, he had had to reject as many as 19 children simply because they had not the strength and development required by the Factory Act, and these numbers were steadily year by year increasing. Another evil he had noticed was that many young children of 12 years of age or thereabouts were beginning to learn to smoke, acquiring the habit from their fathers, and possibly from their mothers also. This was a condition of things which, in his mind, excited painful considerations. What was to become of the factory population if this physical degeneration went on?”

(Mr. Alderman Ferguson, Bolton, was also a Certifying Surgeon under the Acts; Bridges and Holmes, pp. 41-42)

The authors expressed themselves forcibly, that the absence of mothers in the mill, was the cause of the high death-rate of the small children.

Dr. Charles Roberts made a similar report in 1876, on one thousand boys and girls of each age; the principal information is:

Charles Roberts, The Physical Requirements of Factory Children, 1876

| Age | Average Height Boys | Average Height Girls | ||

| 8 | 46.9 | 46.5 | ||

| 9 | 49.0 | 48.4 | ||

| 10 | 50.6 | 49.9 | ||

| 11 | 52.1 | 51.7 | ||

| 12 | 53.8 | 53.2 | ||

| 13 | 55.0 |

“Physical Improvement or Degeneracy of the Population

Few statistics are in existence which help to throw light on this subject. It is generally believed that the population in the manufacturing towns of the North of England is rapidly degenerating, but a comparison of the measurements of stature and weight given in the Report of the Factory Commissioners in 1833, and in the Report to the Local Government Board on “Changes in Hours and Ages of Employment of Children and Young Persons in Textile Factories”, 1873, shows that this is not the case. On the contrary, an examination of Table XXIV, showing these measurements, indicates a slight but uniform increase in stature, and a very large increase in weight, at corresponding ages. The increase in weight amounts to a whole year’s gain, and a child of 9 years of age in 1873 weighed as much as one of 10 years in 1833, one of 10 years as much as one of 11, and one of 11 as much as one of 12 years in the two periods respectively.”

(Anthropometric Committee, 1882/83, p. 298)

STATURE

| Boys | Boys | Girls | Girls | |||||||||||

| 1833 | 1873 | 1833 | 1873 | |||||||||||

| Age | No. | Inches | No. | Inches | Dif. | No. | Inches | No. | Inches | Dif. | ||||

| 9 | 17 | 48.1 | 126 | 48.3 | +0.2 | 30 | 48.0 | 114 | 48.3 | +0.3 | ||||

| 10 | 48 | 49.8 | 256 | 49.8 | 0.0 | 41 | 49.6 | 201 | 50.3 | +0.7 | ||||

| 11 | 53 | 51.3 | 196 | 51.6 | +0.3 | 51 | 51.1 | 174 | 51.2 | +0.1 | ||||

| 12 | 53 | 53.3 | 175 | 53.3 | 0.0 | 80 | 53.7 |

WEIGHT

| Boys | Boys | Girls | Girls | |||||||||||

| 1833 | 1873 | 1833 | 1873 | |||||||||||

| Age | No. | Lbs. | No. | Lbs. | Dif. | No. | Lbs. | No. | Lbs. | Dif. | ||||

| 9 | 17 | 51.8 | 136 | 58.1 | +6.3 | 30 | 51.3 | 137 | 55.9 | +4.6 | ||||

| 10 | 48 | 57.0 | 247 | 60.2 | +3.2 | 41 | 54.8 | 179 | 60.6 | +5.8 | ||||

| 11 | 53 | 61.8 | 189 | 67.7 | +5.9 | 63 | 59.7 | 180 | 65.4 | +5.7 | ||||

| 12 | 42 | 66.0 | 167 | 69.8 | +3.8 | 80 | 66.1 |

Table XXIV – Showing the average Stature and Weight of Factory Children at an interval of 40 years, 1833-1873 (Stanway and Roberts). (But actually it is Stanway and Bridges/Holmes)

| Boys | Boys | Girls | Girls | |||||||||||

| 1833 | 1873 | 1833 | 1873 | |||||||||||

| Age | No. | Inches | No. | Inches | Dif. | No. | Inches | No. | Inches | Dif. | ||||

| 9 | 41 | 48.6 | 60 | 49.1 | +0.5 | 43 | 48.4 | 30 | 49.4 | +1.0 | ||||

| 10 | 28 | 50.6 | 50 | 51.0 | +0.4 | 38 | 49.4 | 30 | 49.8 | +0.4 | ||||

| 11 | 25 | 51.0 | 30 | 52.6 | +1.6 | 29 | 52.1 | 30 | 52.8 | +0.7 | ||||

| 12 | 20 | 53.0 | 20 | 53.6 | +0.6 | 27 | 53.7 | 17 | 53.4 | -0.3 |

| Boys | Boys | Girls | Girls | |||||||||||

| 1833 | 1873 | 1833 | 1873 | |||||||||||

| Age | No. | Lbs. | No. | Lbs. | Dif. | No. | Lbs. | No. | Lbs. | Dif. | ||||

| 9 | 41 | 53.3 | 60 | 59.4 | +6.1 | 43 | 50.4 | 30 | 57.8 | +7.4 | ||||

| 10 | 28 | 60.3 | 50 | 63.8 | +3.5 | 38 | 54.4 | 30 | 60.8 | +6.4 | ||||

| 11 | 25 | 58.4 | 30 | 70.2 | +11.8 | 29 | 61.1 | 30 | 69.0 | +7.9 | ||||

| 12 | 20 | 67.2 | 20 | 70.9 | +3.7 | 27 | 66.1 | 17 | 70.5 | +4.4 |

This shows that apparently the natural increase in the general child population from 1833 was 1873 was visible, but that there was a negative effect on the factory children.

The heights and weights of children of 11 years old showed the following progression during the century:

| Date | Segment | Place | Investigator | Boys 11 yrs. Height ins. | Weight lbs. | Girls11 yrs. Height ins. | Weight lbs. |

| 1833 | Factory and non-Factory Children | Manchester and Stockport | Stanway, Cowell | 51.2 | 60.7 | 51.5 | 60.2 |

| 1836 | Factory Children | Lancashire, Cheshire, West Riding | Horner | 50.8 | 50.7 | ||

| 1836 | Factory Children | Leeds | Baker | 50 | 50 ¼ | ||

| 1836 | Factory Children | Preston | Harrison | 50 ½ | 51 ¼ | ||

| 1876 | Factory Districts | Lancashire, Cheshire, West Riding | Roberts | 51.2 | 68.1 | 51.8 | 66.2 |

| 1878-82 | Labouring Classes | Country | Anthrop. Committee | 52.3 | 72.2 | 52.5 | 67.1 |

| 1878-82 | Artisan Families | Towns | Anthrop. Committee | 52.7 | 69.0 | 51.5 | 66.8 |

Extracted from:

M. N. Karn, Summary of Results of Investigations into the Height and Weight of Children of the British Working Classes during the last Hundred Years (1936)

The boys showed – similarly to the adult men – a considerable differentiation in stature in function of the social / economic level.

| Average height, inches,11-12 years | ||

| All Observations | 52.6 | |

| Public Schools | Country | 55.0 |

| Middle-class Schools | Upper Towns | 53.8 |

| Middle-class Schools | Lower Towns | 53.7 |

| Elementary Schools | Agricultural labourers Country | 53.0 |

| Elementary Schools | ArtisansTowns | 52.6 |

| Elementary Schools | Factories and Workshops Country | 52.2 |

| Elementary Schools | Factories and Workshops Towns | 51.6 |

| Military Asylums | 51.2 | |

| Industrial Schools | 50.0 |

Anthropomorphic Committee, 1882-1883, Table XIII: Table showing the Relative Statures of Boys of the age of 11 to 12 years, under different physical and social conditions of life.

Convicts

The above pieces of information about the heights of men, women, and children from the general population only refer to a few individual dates. This is because there was no continuous measurement of a group, year by year. So we cannot show a graph of heights per year, and cannot demonstrate a possible connection between average heights and the standard of living (income, food, sanitation) in some short periods.

There were two segments of the population, who were under the control of the authorities, and whose height was measured, when they came to the notice of the authorities. These were the convicts (those who were transported, and those who were incarcerated in the United Kingdom), and the enlisted soldiers.

In these cases, as we have figures of heights for the average of the segment at a given date (incarceration; enlistment), we can classify the heights by birth yearof the individual person, and then calculate an average height for all of the persons of the resultant year.

The absolute figures of the average heights of the convicts and of the soldiers are not the same as those of the general population, they are generally from 1 to 2 inches less. But we may assume that the movements in each of the segments “mirror” the movements for the general population (if we had them).

The idea behind this arithmetical process is that the external factors (economics, food, sanitation, epidemics) which could affect the final height of a person, would have occurred with respect to the person in the period from 0 to 15 years old. So hopefully we can identify changes in the external factors, through the movements in the average heights. This is the fundamental premise of “Anthropomorphic History”; see Bernard Harris, Anthropometric History and the Measurement of Wellbeing, Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 19 (2021).

This analysis is all the more important for studies of the period 1770 to 1840, as we have no continuous yearly series of data about incomes or about food consumption per person, based on contemporary documentation.

The data for the convicts are from the records of the administration of the shipping of the convicts to Australia, from the records of the prison services, and from publications of the police. These data have been incorporated into an interconnected data base “The Digital Panopticon”, digitalpanopticon.org, constructed in the last twenty years by a group led by Barry Godfrey, Robert Shoemaker, Tim Hitchcock, Deborah Oxley and Hamish Maxwell Stewart. The academic investigations commented below have been made by researchers using the original registers of the authorities, or the Digital Panopticon.

The series of heights from the different researchers for the period in question, are as follows. We see that there is little movement from year to year, except that there is a small decrement around the birth years 1830 to 1850.

Nicholas Convicts M:

Stephen Nicholas and Richard H. Steckel; Heights and Living Standards of English Workers during the Early Years of Industrialization, 1770-1815; The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 51, No. 4 (Dec. 1991), pp. 937-957, p. 948, figure 3.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2123399

Weber Convicts M:

Jacob P. Weber; Patterns in British Height, 1770-1845; Term Paper, 2018, Berkeley; Figure 5, Long-term height trends, men and women, age 20-70, 5-year centered average; p. 5

https://delong.typepad.com/jacob-p.-weber-heightpaperfinal-x.pdf

Johnson Convicts M:

Paul Johnson and Stephen Nicholas, 1992; Health and Welfare of Women in the United Kingdom, 1785-1920; In: Richard H. Steckel and Roderick Floud, Health and Welfare during Industrialization, 1997; Fig. 6.11. Rural and urban male and female criminal heights, ages 19-49, p. 222; Source: Alphabetical Register of Habitual Criminals

http://www.nber.org/chapters/c7432

Panopticon Convicts M:

Extracted from the Digital Panopticon, by the present author, men ages 20-49.

Weber Convicts F:

Weber, Jacob P., 2018, op. cit.

Johnson Convicts F:

Johnson and Nicholas, 1992, op. cit.

Panopticon Convicts F:

Extracted from the Digital Panopticon, by the present author, women ages 20-49.

The convicts were about two inches shorter than the general population.

“An impression is often prevalent that the criminal population consists of persons of the greatest physical strength; but speaking from observation of the adult prisoners from the towns and convicts in the hulks, they are in general below the average standard of height.”

(Edwin Chadwick, Inquiry into the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population…, 1842, p. 202)

The men and women in the criminal registers came predominantly from London and the northern industrial towns.

| Place of birth Men 1830 | Place of birth Women 1830 | Place of birth Men 1860 | Place of birth Women 1860 | |||||||

| Total England | 327 | Total England | 116 | Total England | 1,005 | Total England | 167 | |||

| London | 100 | London | 24 | London | 386 | London | 35 | |||

| Manchester | 24 | Manchester | 10 | Manchester | 74 | Manchester | 25 | |||

| Liverpool | 30 | Liverpool | 8 | Liverpool | 56 | Liverpool | 21 | |||

| Leeds | 8 | Leeds | 1 | Leeds | 31 | Leeds | 6 | |||

| Birmingham | 21 | Birmingham | 11 | Birmingham | 66 | Birmingham | 4 | |||

| Sheffield | 1 | Sheffield | 3 | Sheffield | 21 | Sheffield | 10 | |||

| Bristol | 7 | Bristol | 4 | Bristol | 25 | Bristol | 1 | |||

| Newcastle | 8 | Newcastle | 2 | Newcastle | 13 | Newcastle | 1 | |||

| Nottingham | 7 | Nottingham | 2 | Nottingham | 29 | Nottingham | 5 | |||

| Other | 121 | Other | 51 | Other | 304 | Other | 59 |

We can say from the occupations given, that they work in industry. This would explain why they were shorter than the general population, because they came from factory occupations, and the factory workers were about 1 ½ inches shorter than the average of the country.

| Average height,inches, 25-30 years | ||

| Total Population | 67.4 | |

| Class I | Professional Classes | 69.1 |

| Class II | Commercial Classes, Clerks and Shopkeepers | 67.9 |

| Class III | Labouring Classes: Agricultural, Miners, Sailors, Shopkeepers | 67.5 |

| Class IV | Artisanal Classes, living in Towns | 66.6 |

| Class V | Sedentary Occupations: Factory Operatives, Tailors | 65.9 |

Report of the Anthropometric Committee, 1882-83

For the years 1834 to 1845, in England and Wales, there were about 25,000 offenses per year, of which about 20,000 were “offenses against property, committed without violence”.

(Porter, Progress of the Nation, 1847, p. 652)

About 75 % of the criminals in the given period were of ages from 16 to 40.

(Porter, op. cit., p. 655)

The percentages of literacy were:

| Males | Females | ||

| Neither read nor write | 32 | 37 | |

| Read only; or read and write imperfectly | 55 | 57 | |

| Read and write well | 9 | 4 | |

| Superior instruction | 1 | 0 | |

| Instruction not ascertained | 3 | 2 |

These are considerably less than the percentages for factory workers at that time.

The Rev. John Clay, chaplain of the prison at Preston, interviewed 1000 new prisoners from 1832 to 1837, asking them the reasons why they committed the crime; the results were:

Drunkenness (455), Want and Distress (76), Temptation (48), Neglect of Parents (6), Combination (11), Weak Intellects (8), Idleness and bad Company (88), Idleness and Ignorance (18), Confirmed bad Habits (38), Alleged Innocence; and various or uncertain Causes (252).

The major types of crime committed, changed from the first half to the second half of the 19thcentury:

Trials at the Old Bailey

| Percentage 1835–1854 | Percentage 1855–1913 | |

| Simple larceny | 35.2 | 11.7 |

| Stealing fromone’s master | 14.7 | 4.6 |

| Coining | 5.2 | 11.7 |

| Burglary | 3.1 | 9.7 |

| Fraud | 2.4 | 10.3 |

Vickers, Ziebarth, 2016, p. 200

The persons committed to prison or to transportation were members of the lower class of workers, and were generally from London and the northern industrial towns. They would not have been of the same height of the generality of the population, but it is reasonable to suppose that their heights would have moved “in step” with those of the average of the population.

SOLDIERS

In reference to the question of whether the soldiers were representative of the general male population, as to their heights, the answer is a qualified «Yes»:

- no one went to enter the army because it was a good option;

- the men who presented themselves, all had some sort of problem, either personal or financial; many were unemployed at the moment of recruitment (especially the case from 1870 onwards);

- the army solved their problems, because it gave them, wages, food and a bed, guaranteed for years;

- the occupations were 60 % labourers, 15 % manufacturing artisans, 18 % carpenters, smiths, weavers, etc. (but very few factory workers).

The main difficulty in using the data of the heights of these men during the whole of the period, is that there was a differentiation in the army recruitment policies, in times of war and in times of peace. In peacetime, the army could be stringent about the minimum height standard, because they did not need many additional soldiers; in wartime, they took everyone, and thus in this case, the heights of the recruits corresponded closely to the profile of the general population.

This means that in the war years the histogram of heights was that of the standard distribution curve. In years of peace the distribution curve was missing a part or the whole of the “left wing”, and so the average height of the men effectively recruited was higher than the average height of the segment of men who wished to enter the army. The different procedures for correcting this have caused grave contradictions between the different investigations.

In the Annex we can see a simple form of calculation to approximate the real average for the underlying segment. This calculates an adjustment in each decade. Six of fifteen decades have perfect histograms and thus do not need any adjustment. The maximum adjustment calculated for a decade is minus 1.3 inches.

The average heights at recruitment date are from 5 ft. 6 ins. to 5 ft. 7 1/2 ins. These would be a little less than the average of the men “walking along the street”, because about 50 % of the recruits entered at 18 to 22 years old, and they would still be about one inch shorter than at the average age of the population.

The men who went to the Recruiting Office (or to the public house, where the Recruiting Sergeants were generally stationed!), went because they had problems, and the army could solve them:

«Class of the population from which recruits are procured:

Agricultural labourers generally enter the army in consequence of some family difficulty or discord, or some scrape in which they are involved, or from want of work; and it is alleged by competent authority that they become the most trustworthy soldiers. Recruits who are enlisted in the manufacturing districts or the large towns are frequently idle and dissolute, and require all the means in the power of their officers to correct the intemperate and vicious habits in which they have indulged, and to enforce subordination.»

“The condition of a soldier is very little calculated to induce an industrious man, who can obtain subsistence in other way, to embrace it; consequently, those who enter the service are commonly thoughtless youths, petty delinquents, men of indolent habits, persons who are unable to procure work, or are in very indigent circumstances……. Experience holds out no hope, that, under existing circumstances, any but the worst educated, and certainly not the best conducted, of the manual labour rank of the population, will deliberately make choice of a military profession.”

(Marshall, p. 8)

“On looking into the matter, very serious doubts arose whether any one ever enlisted into the Army for the purpose of making it a regular profession for life. He found that there were some classes of their recruits who had readily gone into the ranks, not with any view to the future, but rather with a view of escaping present distress. Their ranks were very much recruited by the idle and the dissolute, who thought that in the life of a soldier they would find that idleness and dissipation congenial to their dispositions. It was too often the case, that the prodigal sought in the Army a refuge from his improvidence; and lads who had got into disgrace, immediately had recourse to enlistment in order in order to avoid their masters. With that class voluntary enlistment was at an end.”

(Mr. Fox Maule, M. P., The Army Service Bill, Hansard, House of Commons, 22 March 1847, vol. 91, p. 273)

“In 1859, the Adjutant-General of the Army told a Royal Commission on Recruiting that there were “very few men who enlisted for the love of being a soldier: it is a very rare exception”. Seven years later his successor told another Royal Commission: “I am afraid it is drink and being hard up which leads a great many to enlist”. Recruiting Sergeant William Knibbs of the 17th Lancers found that of the many hundreds of recruits he had enlisted between 1851 and 1859, “not one in fifty has money in his pocket when he comes to us – and then I must ask him, “have you a bed to go to?” “No.” “Well, I will find you a bed.” Sometimes I must find him his food.”

(Marquess of Anglesey, 1975, p. 260)

So we see that the Army was not really a part of the labour market, but in fact a form of social support for the unemployed / unemployable. Rather like the workhouse.

It was usually understood, that a new recruit would put on about 7 pounds weight in the first six months, due to the food and the exercise. This means that the Body Mass Index, if calculated with the initial weight, has to be adjusted in each case.

The disadvantages of life in the army were: the long contract term (up to 1835, 21 years; afterwards, 12 years); for those who were stationed in India this would be a long time without seeing their family; possibility of death in battle; possibility of death from disease in the Tropics; military discipline.

The advantages of life in the army, for this class of men, were: food (3/4 pound of meat and one pound of bread per day), bed, clothing (uniform), wages of one shilling a day, medical care, comradeship.

The health of recruits (i.e. those effectively accepted) was in general bad. The investigation of Mitchell (2006) analyzes a document of the Household Cavalry Museum: “Royal Horse Guards Vaccinations and Inspection of Recruits 1817-1851”.

The Household Cavalry in general had a good level of recruits, who had to be above 5 ft. 11 ins., and usually came from the artisan and skilled labour class. But the men who presented themselves were usually thin. For example, the instruction was that a man of 20 years old, had to weigh over 132 lbs. to be accepted. Many of the accepted recruits were described as “malnourished”, “emaciated”, or “of a feeble constitution.»

For a visual idea of the soldiers in the 1840’s, see YouTube “Earliest photographs of British soldiers from the 1840’s”:

a

A sergeant reading the Order of the Day to soldiers of the 42nd (Highland) Regiment of Foot, Edinburgh Castle, April 9th, 1846. Hill and Adamson.

aAnd from the 1850’s, photos of the Crimean War:

aThe 3rd (East Kent) Regiment (The Buffs) in the Crimea, 1855.

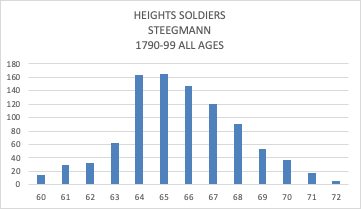

The first investigation of heights is from Steegmann (1985). It is an analysis of the registers of the 54th (West Norfolk) Regiment from 1762 to 1799. The information given in the paper is by birth-year, and the soldiers were born in 1749 to 1778. The data include English and Irish men, but the average height was the same for the two nationalities. Of 1100 soldiers, 950 are from the period 1790-1799. The majority had been agricultural labourers.

Mature stature for men recruited in 1762-1775 was 169.9 cm (5 ft. 6.9 ins.), for those recruited in 1776-1782 it was 169.5 cm. (5 ft. 6.7 ins.), in 1783-1789 it was 172.6 cm. (5 ft. 7.9 in.), and in 1790-1799 it was 167.5 cm. (5 ft. 5.9 ins.). The average heights at enlistment were less in war-time years (we suppose the military authorities were less «choosy»). The most frequent ages at enlistment were 18, 19 and 20 years, 40 % of the total, and their height was around 167.7 cm. (5 ft. 6.0 ins.)

Movements in adult height appear to reflect the food situation at the respective birth dates.

The following two graphs show the distribution of heights in the period 1790 to 1799 (wartime); first the totality of recruits, and below, the men of over 21 years. We note that the graph below is a complete distribution curve.

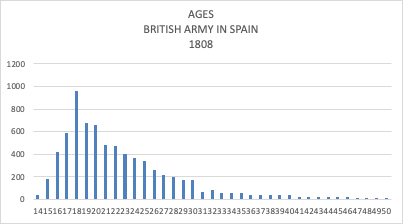

The next information is the British Soldier Compendium (constructed by Edward Coss from data in the National Archives), referring to 7,300 of the British Soldiers in Spain under Wellington. The soldiers who enlisted in the Napoleonic Wars were about 300,000 at any one time, so we can take these as representative of the general population (i.e. they were not a specific segment). The Army authorities during the war needed to have a maximum number of soldiers, so they did not impose any “minimum height standards” at that time. Thus we see that the distribution is a well-formed “bell curve”, i.e. there is no “truncation” of the left tail, which would be visible if there were effectively minimum height standards.

Coss, Figure 1, Age distribution of all enlistees

a

For the period 1860 to 1880, the average height of the recruits was continuously close to 66 inches. This is corroborated by the fact that the authorities had to reduce the minimum height limit from 65 inches in 1872 to 64 inches in 1880 and to 63 inches in 1883, because they were not able to find enough recruits of the requisite heights.

From 1870, the military authorities were having problems to find the number of recruits necessary for the planned operations volume, and from 1880 the proportion of smaller or lighter recruits began to increase.

“The number of men who were so small in frame as to be useless as soldiers was on the increase, he regretted to say; and last year there were 174 per 1,000 who only weighed 8 st. 8 lbs. What was 8 st. 8 lbs. for a soldier? It was the weight of a Derby jockey, and not of a man fit for a campaign.”

(Sir Walter B. Battelot, M. P., Army (Recruiting) – “Waste” of the Army – Observations, Hansard, House of Commons Debate, 01 June 1883, vol. 279, cc 1529)

“But if anyone would take the trouble to see for themselves the actual material of these figures, he would find a lamentable and a pitiable exhibition. To call them soldiers was a misnomer. They were boys of 16 and 17, enlisted under false representations made by themselves as to age, boys of not necessarily more than 5 feet 3 inches in height, or 32 inches in chest measurement, by a recent Warrant. ….