- Friedrich Engels and “The Condition of the Working Classes in England in 1844”

- November 2025

- [Page references of English texts are to the first English language edition, 1887, translation by Florence Kelley Wischnewetzky, authorized by Friedrich Engels, https://archive.org/details/conditionofworki00enge_0]

- [Page references of German texts are to «Die Lage der arbeitenden Klasse in England», (Zweite Auflage), 1848, Google = «Hathitrust Die Lage der arbeitenden Klasse in England 1848»]

- Contents

- Engels gave Marx diametrically opposed information

- Lack of information from Working Class persons

- The data which Engels takes over from Dr. Kay’s booklet, referred only to the Township, which had a large proportion of Irish;

- Consumption and Quality of Meat;

- Wages compared with Food Costs;

- Number of Rooms per House;

- Different Levels of Housing in Manchester;

- Poor Areas of the City;

- Health and Hospitals;

- Geography of Manchester;

- Bolton;

- The Potteries;

- Unfounded Accusations against progressive Mill-owners;

- Financial and Housing Properties;

- Reported Indifference to Religion;

- Physical Aspect of the Workmen;

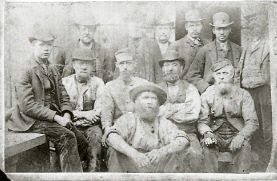

- Group of Manchester Workmen 1848 (photograph);

- Reading and Writing;

- Positive Effects of the Industrial Revolution, according to Engels;

- Error in the «Sob Story»;

- Engels’ Intention and Tactic;

- Contemporary Criticism of the Book by German Academics.

INTRODUCTION

It is / was difficult to formulate a simple description of Manchester in 1844, with reference to its working-class persons. There were large differences between the better-situated workers and the really poor.

As we shall see in the contemporary evidence adduced in this document, a large part of the factory population in the 1840’s had a decent life, with earnings of 20 to 30 shillings per family, enough bread and meat, reasonable housing, and without bad treatment in their workplace. A large minority of the working-class were treated very badly, either by their employers or by the economic and social system; these people had insufficient incomes to eat enough, could not be sure that they would have income in the next week, lived in cellars or in small badly-built houses, with inexistent sanitary arrangements, sometimes with 10 persons per house. In addition to the bad sanitary conditions, the rooms of the houses of the poor were often in horrible conditions, because the inhabitants had very uncivilized habits.

Friedrich Engels gives us – as it were – a “skewed” picture:

| “Such are the various working-people’s quarters of Manchester as I had occasion to observe them personally during twenty months. If we briefly formulate the result of our wanderings, we must admit that 350,000 working-people of Manchester and its environs live, almost all of them, in wretched, damp, filthy cottages, that the streets which surround them are usually in the most miserable and filthy condition, laid out without the slightest reference to ventilation, with reference solely to the profit secured by the contractor. In a word, we must confess that in the working-men’s dwellings of Manchester, no cleanliness, no convenience, and consequently no comfortable family life is possible; that in such dwellings only a physically degenerate race, robbed of all humanity, degraded, reduced morally and physically to bestiality, could feel comfortable and at home.” (Chapter II, The Great Towns, p. 43) |

The explanation for the difference is:

| a) the majority of people had an average or good life; b) a large minority of the people had a bad or a very bad life; c) the individual cases presented by Engels, as to the horrible circumstances of the poor, are practically all probably true; d) Engels carefully selected the information for his book, to give a uniformly negative impression. |

In his Preface (German Edition: Vorwort S. 10; this Preface does not appear in the first English Edition), Engels takes a tactical decision, as to the words to be used in referring to the persons of the working class:

| “Similarly, I have continually used the expressions workingmen (Arbeiter) and proletarians, working-class, propertyless class and proletariat as equivalents.” |

This enables him to:

- suppose that all of these persons have roughly the same (low) weekly income, and food consumption;

- suppose that all of these persons have no property;

- suppose that all of these persons live in the same low level of housing;

- suppose that the regions of the towns where each part of this group lives, are all similar.

This also has the effect on ourselves, the readers, that when we form a “mental image” of one of the groups, we easily make it extensible to the other groups.

But we will see that in Manchester at least, in Engels’ time, there is a geographical division between the poor, who live in the Township (old, central area), and the workers with good jobs, who live in the surrounding suburbs (which are not the “upper class” suburbs!).

There is also a division given by the wage levels. It would appear that Engels does not want to admit the existence of a group of better-paid and better-employed workers.

I. Engels gave Marx diametrically opposed information

First we show that Engels did know that the working class with employment ate well, ……… :

| “From Lancashire, December 20. The condition of the working class in England is becoming daily more precarious. At the moment, true, it does not seem to be so bad; most people in the textile districts have work; for every 10 workers in Manchester there is perhaps only one unemployed, the proportion is probably the same in Bolton and Birmingham, and when the English worker is employed he is satisfied. And he can well be satisfied, at any rate the textile worker, if he compares his lot with the fate of his comrades in Germany and France. The worker there earns just enough to allow him to live on bread and potatoes; he is lucky if he can buy meat once a week. Here he eats beef every day and gets a more nourishing joint for his money than the richest man in Germany. He drinks tea twice a day and still has enough money left over to be able to drink a glass of porter at midday and brandy and water in the evening. This is how most of the Manchester workers live who work a twelve-hour day.” (Underline by this author) (Engels, Friederich (signed as “X”) The Condition of the Working Class in England Written December 20, 1842, Published in the “Rheinische Zeitung”, No. 359, December 25, 1842 Marx and Engels Collected Works, digital edition Lawrence & Wishart, 2010, Volume 2, p. 378; search, specifying «1842») |

[This is Engels’ first month in England, and he does not seem to be surprised!]

…… had good incomes, ….. :

| “…. But the colonies are far from being large enough to consume all the products of England’s immense industry, while everywhere else English industry is being increasingly ousted by the German and French. The blame for this, of course, does not lie with English industry, but with the system of protective tariffs, which has made the prices of all prime necessities, and with them wages, disproportionately high. But these wages also make the prices of English products extremely high compared with those of continental industry. Thus, England cannot escape the necessity of restricting her industry.” (Underline by this author) (Engels, Friederich (signed as “X”), The Internal Crises, Written November 30, 1842. Published in the “Rheinische Zeitung”, No. 344, December 10, 1842, Marx and Engels Collected Works, digital edition Lawrence & Wishart, 2010, Volume 2, p. 373) |

…… were well informed about politics, and used their free time well ….. :

| “While the Church of England lived in luxury, the Socialists did an incredible amount to educate the working classes in England. At first one cannot get over one’s surprise on hearing in the Hall of Science the most ordinary workers speaking with a clear understanding on political, religious and social affairs; but when one comes across the remarkable popular pamphlets and hears the lecturers of the Socialists, for example Watts in Manchester, one ceases to be surprised. The workers now have good, cheap editions of translations of the French philosophical works of the last century, chiefly Rousseau’s Contrat social, the Système de la Nature and various works by Voltaire, and in addition the exposition of communist principles in penny and twopenny pamphlets and in the journals. The workers also have in their hands cheap editions of the writings of Thomas Paine and Shelley. Furthermore, there are also the Sunday lectures, which are very diligently attended; thus during my stay in Manchester I saw the Communist Hall [actually “Manchester Hall of Science”], which holds about 3,000 people, crowded every Sunday, and I heard there speeches which have a direct effect, which are made from the special viewpoint of the people, and in which witty remarks against the clergy occur. It happens frequently that Christianity is directly attacked and Christians are called “our enemies”. In their form, these meetings partly resemble church gatherings; in the gallery a choir accompanied by an orchestra sings social hymns; these consist of semi-religious or wholly religious melodies with communist words, during which the audience stands. Then, quite nonchalantly, without removing his hat, a lecturer comes on to the platform, on which there is a table and chairs; after raising his hat by way of greeting those present, he takes off his overcoat and then sits down and delivers his address, which usually gives much occasion for laughter, for in these speeches the English intellect expresses itself in superabundant humour. In one corner of the hall is a stall where books and pamphlets are sold and in another a booth with oranges and refreshments, where everyone can obtain what he needs or to which he can withdraw if the speech bores him. From time to time tea-parties are arranged on Sunday evenings at which people of both sexes, of all ages and classes, sit together and partake of the usual supper of tea and sandwiches; on working days dances and concerts are often held in the hall, where people have a very jolly time; the hall also has a café.” (Engels, Friederich, Letters from London, Schweizerischer Republikaner No. 46, June 9, 1843, Letter III, Marx and Engels Collected Works, digital edition Lawrence & Wishart, 2010, Volume 3, p. 387) |

…… and, far from working very long hours in Engels’ times, in 1843 had the working week reduced from 6 days to 5 ½ days, by a voluntary decision of the manufacturers and shop owners in Manchester.

(Manchester Courier, and Lancashire General Advertiser, Saturday, November 4th, 1843; http://www.genesreunited.co.za/searchbna/viewrecord/bl/0000206/18431104/054/0005; British Newspaper Archive)

This occurred while Engels was working in Manchester, in the sales area of a cotton mill.

II. Lack of Information from Working Class Persons

Engels apparently spent a considerable proportion of his time, talking with working class and visiting them in their homes.

| “To The Working Classes of Great-Britain, Working Men! to you I dedicate a work, in which I have tried to lay before my German Countrymen a faithful picture of your condition, of your sufferings and struggles, of your hopes and prospects. I have lived long enough amidst you to know something about your circumstances; I have devoted to their knowledge my most serious attention, I have studied the various official and non-official documents as far as I was able to get hold of them –I have not been satisfied with this, I wanted more than a mere abstract knowledge of my subject, I wanted to see you in your own homes, to observe you in your everyday life, to chat with you on your condition and grievances, to witness your struggles against the social and political power of your oppressors. I have done so: I forsook the company and the dinner-parties, the port-wine and champagne of the middle-classes, and devoted my leisure-hours almost exclusively to the intercourse with plain Working-Men; …” (Dedication in the original German version of 1845, p. 3, given there in English) (Not present in the English language version of 1887) |

We do not have any information from workers, or about them, or about their housing conditions. There is not one quote from a working class person.

These would have been very useful as a form of Field Research. We could have statistical data as to the incomes of the persons, rate of illness, size and number of rooms, hours worked, quality of their food, or expressions as to whether they were happy or not.

But these data have not reached us.

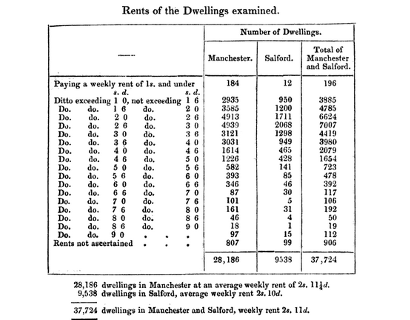

III. The data which Engels takes over from Dr. Kay’s booklet referred only to the Township, which had a large proportion of Irish

A large part of the pessimistic descriptions of the workers’ living conditions in Manchester is taken over from the short book “The Moral and Physical Condition of the Working Classes employed in the Cotton Manufacture in Manchester” (1832) by Dr. James Kay. The booklet also gives detailed quantitative data as to the sanitation problems in each Police District. This would seem to give evidential bases for Engels’ statement about the 350,000 people in Greater Manchester living in horrible conditions. But Dr. Kay’s book does not refer to the totality of the conurbation (354,000 persons in the 1841 Census), but only to the Township (163,000). Engels did say, that the 6,951 houses examined were «- naturally in Manchester proper alone, Salford and the other suburbs being excluded». But he did not make it clear, that the other suburbs had better standards of living than the Township.

(Taken from the Prologue of Dr. Kay’s booklet)

Obviously, Engels knew that Dr. Kay’s booklet referred only to the Township (it gives data only for the 14 Police Districts). He had no excuse, as he lived in Manchester for nearly two years.

But, further, the proportion of the population in the suburbs increased from 1832 to 1842:

“The great disparity of increase of the three districts under notice [Manchester, Salford, Chorlton] is to be attributed to the centre of Manchester becoming, from year to year, less occupied as family dwellings; for, though its multitude of compact buildings are like a bee-hive by day, yet they are household residences of a very few; the great body of occupiers living in the outskirts, or in the more airy parts of other unions. The comparatively diminished rate of increase in Manchester may, in some degree, be affected by the working classes themselves gradually forsaking their cellar and other confined buildings for the more clean and airy cottages, which have of late years been so numerously built out of the township, as in Chorlton and Hulme. The greater increase in the other two unions are to be accounted for on converse circumstances, – from the inhabitants forsaking the interior of the town, and living in the outskirts; either from views of health, economy, or being displaced from their town dwellings by the extension of warehouses and manufacturing establishments.”

(Benjamin Love, The Hand-Book of Manchester, 1842, pp. 24-25)

[Actually, the descriptions of Dr. Kay as to the filthy habits of the workers were exaggerated, as they referred principally to the Irish:

“Have you seen the work of Dr. Kay on the statistics of Manchester, as to the state of the operatives of that town?” “Yes, I know Dr. Kay, and I believe what he says is correct; but he gives the matter as it now stands, knowing nothing of former times; his picture is a very deplorable one. I am assured that my view of it is correct by many Manchester operatives whom I have seen; they inform me that his narration relates almost wholly to the state of the Irish, but that the condition of a vast number of the people was nearly as bad some years ago, as he describes the worst portion of them to be now. Any writer or inquirer will be misled unless he has the means of comparing the present with former times.”

(Mr. Francis Place, political and educational reformer, Evidence to the Select Committee on Education in England and Wales, 1835, p. 72)]

The municipal authorities in Manchester made a large number of improvements in the sanitary condition of the city between 1830 and 1840. They were congratulated in writing by the rapporteur of the “Local Reports on the Sanitary Condition of the Population”, who wrote that they had done more than any other local authority in England.

(Poor Law Commissioners, Local Reports on the Sanitary Condition of the Population, 1840, 17. Lancashire, Cheshire, Derbyshire and Staffordshire, Comment by Charles Mott, Assistant Poor Law Commissioner, p. 243)

IV. Improvements in Sanitary Conditions from 1830 to 1840

The municipal authorities in Manchester made a large number of improvements in the sanitary condition of the city between 1830 and 1840. They were congratulated in writing by the rapporteur of the “Local Reports on the Sanitary Condition of the Population”, who wrote that they had done more than any other local authority in England.6

6 Poor Law Commissioners, Local Reports on the Sanitary Condition of the Population, 1840, 17. Lancashire, Cheshire, Derbyshire and Staffordshire, Comment by Charles Mott, Assistant Poor Law Commissioner.

‘With these difficulties to encounter, too much praise cannot be given to the committee for the great improvements carried into execution by them. Since 1830, more then 32 miles of sewers have been constructed. The total number of streets sewered and paved, or “on the town’s books”, is 480; but there are still 450 unpaved and unsewered streets of sufficient size to come under the operation of the act .…………

10. The labours of the committee [“The Paving and Soughing (sewerage) Committee” of the town-council of Manchester] have not by any means been confined to the wealthy parts of the town, the poor districts having attracted a large, if not the largest share of their attention. And their labours have not been in vain; Dr. Howard and Mr. Leigh, who were intimately acquainted with these districts some years since, from the connection with the infirmary, kindly agreed to inspect the worst conditioned localities with a view to report on their present state. They both express their astonishment at the better appearance of the inhabitants, and of the physical condition of these districts since the time they were accustomed to visit them. A few years back they were unpaved and unsewered, “and in winter the streets in the district of Angel Meadow were trod up into a thick mud 12 to 14 inches deep, and were almost impassable; the cellars of the houses were flooded, and influenza, cholera or fever, prevailed in succession the year round”. The wards of the hospital were filled with cases from this district. Within the last few years, however, almost the whole of the streets have been put into thorough repair by paving and sewering; the footways have been well flagged, and the cellars have been well protected from the inundations to which they were formerly subject. But they show that there are still many evils connected with this district. “In one part a chandlery sends forth its disgusting effluvia, pigsties are dotted up and down, and heaps of filth are poured a precipitous clay bank to lie and rot.”

Dr. Howard and Mr. Leigh visited carefully all the worst districts of the town in which epidemics had formerly prevailed and cholera raged, and they state their general impression as follows: “These localities are those in which the greatest amount of disease was wont to prevail, and the condition of which is yet such as to attract attention. Still, compared with the appearance which they presented seven or eight years ago, their condition would scarcely be censured by those whose recollections of them extended so far back. Within that period they have nearly all been excellently paved and sewered.”

Mr. Bennett, a surgeon and registrar of deaths in the Ancoats district, in alluding to the health of his district not being impaired in late years with severe distress, states that the reason is “because the draining, paving, &c., is so much improved.”’7

7Commissioners for Inquiring into the State of Large Towns and Populous Districts (1845), Appendix Part II, pp. 4-5.

V. «Privies»

| “A Health Commission was appointed at once to investigate these districts, and report upon their condition to the Town Council. … There were inspected, in all, 6,951 houses – naturally in Manchester proper alone, Salford and the other suburbs being excluded. Of these, …. 2,221 were without privies, … Chapter VI, The Great Towns, p. 69 |

These are by no means bad news. According to Dr. Kay’s Tables, 68 % of the houses in the Township had a private “privy”. In general, in industrial towns, 12 to 16 families had to share one “privy”.

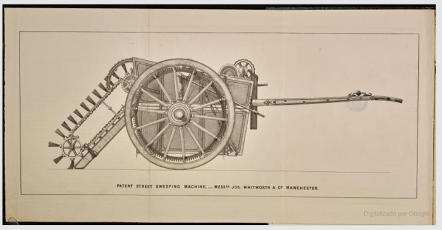

VI. Road Sweeping Machines

| «…. hitherto the principal streets in all the great cities, as well as the crossings, have been swept by people out of work, and employed by the Poor Law Guardians or the municipal authorities for the purpose. Now, however, a machine has been invented which rattles through the streets daily, and has spoiled this source of income for the unemployed.» Chapter III, Competition, p. 58 |

The reproach to be made to Engels, in this respect, is that he does not mention the resulting improvement in daily life, and in health, for the population, starting in 1843. The accumulated general filth in the streets of the working-class areas had reached considerable heights.

The booklet emitted by the company, quotes Edwin Chadwick, who himself quotes the medical officers in Manchester and Leeds, among others:

«That the filthy and disgraceful state of many of the streets in these densely populated and neglected parts of the town where the indigent poor reside, cannot fail to exercise a most baneful influence over their health, is an inference which experience has fully proved to be well founded; and no fact is better established than that a large proportion of the causes of fever which occur in Manchester, originate in these situations. Of the 182 patients admitted into the temporary fever hospital in Balloon-street, 135 at least come from unpaved or otherwise filthy streets, or from confined and dirty courts and alleys. Many of the streets in which cases of fever are common are so deep in mire, or so full of hollows and heaps of refuse that the vehicle used for conveying the patients to the House of Recovery often cannot be driven along them, and the patients are obliged to be carried to it from considerable distances. Whole streets in these quarters are unpaved and without drains or main-sewers, are worn into deep ruts and holes, in which water constantly stagnates, and are so covered with refuse and excrementitious matter as to be almost impassible from depth of mud, and intolerable from stench. In the narrow lanes, confined courts and alleys, leading from these, similar nuisances exist, if possible, to a still greater extent; and as ventilation is here more obstructed their effects are still more pernicious.»8

«The surface of these streets is considerably elevated by accumulated ashes and filth, untouched by any scavenger; they form nuclei of disease exhaled from a thousand sources. Here and there stagnant water, and channels so offensive they have been declared to be unbearable, lie under the doorways of the uncomplaining poor; and privies so laden with ashes and excrementitious matter, as to be unusable prevail, till the streets themselves from deposits of this description; in short, there is generally pervading these localities a want of the common conveniences of life.”’9

8Poor Law Commissioners, Local Reports on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population (1842), Manchester, Dr. Baron Howard, p. 305.

9Poor Law Commissioners, Local Reports …, Leeds, Mr. Baker, pp. 352-353

“33. These remarks apply only to the state of Manchester when I first undertook its examination; but since then the whole system has been altered. Arrangements are now made by which the street-cleansing machine sweeps the streets twice as often as formerly, at a diminished cost of 500 l. Much attention paid to the efficiency of this machine enables me to state with confidence, that the streets of Manchester are kept much more cleanly [sic.] than under the old system of hand labour.”10

We see that as the streets are kept clean, the last column (“No. of streets containing heaps of refuse, stagnant ponds, ordure, &c.”) of Dr. Kay´s Table 1, were it calculated to the year 1844, should show a zero number. But Engels, reporting on the year 1844, does not rectify these fields. And obviously, he walked these streets every day.

10Commissioners for Inquiring into the State of Large Towns and Populous Districts (1845), Appendix Part II, p. 12.

REPORT ON THE PATENT ROAD AND STREET CLEANSING [SIC.] MACHINE

[It is suggested to read pages 1 to 15 of the report in Google]

“THE ROAD AND STREET CLEANSING CO., has been formed to carry into general operation throughout the United Kingdom, the Patent Sweeping Machine invented by Mr. Joseph Whitworth, of Manchester. More than twelve months have elapsed since the machine was first set to work in that town, and during the greater part of that time it has been used throughout an extensive district, under the immediate direction of the Company.

In March, 1842, a part of the Township of Manchester was assigned by the Commissioners of Police for trial of the machine, and a contract was entered into for working it therein during three months. The district included several principal thoroughfares, and contained upwards of 30,000 square yards of street surface. By the terms of the contract, the surface was to be cleaned three times oftener than under the old system, for three-fourths of the cost, or at one-fourth the former rate.

The district in question soon presented a striking contrast with the other parts of the Town, and before the contract expired, a memorial for its renewal and extension, signed by more than one hundred of the principal inhabitants, was presented to the Commissioners.

The contract was accordingly renewed for twelve months, and the district extended to include 90,000 square yards.”11

11Google = “Report on the Patent Road and Street Cleansing [sic.] Machine”

VII. Consumption and Quality of Meat

| “As with clothing, so with food. The workers get what is too bad for the property holding classes. In the great towns of England everything may be had of the best, but it costs money; and the workman, who must keep house on a couple of pence, cannot afford much expense. Moreover, he usually receives his wages on a Saturday evening, for although a beginning has been made in the payment of wages on Friday, this excellent arrangement is by no means universal; and so he comes to market at five or even seven o´clock, whence the buyers of the middle class have had the best choice during the morning when the market teems with the best of everything. But, when the workers reach it, the best has vanished, and, if it was still there, they would probably not be able to buy it. The potatoes which the workers buy are usually poor, the vegetables wilted, the cheese old and of poor quality, the bacon rancid, the meat lean, tough, taken from old, often diseased cattle, or such as have died a natural death, and not fresh even then, often half decayed.” (Chapter I, The Great Towns, pp. 46-47) |

Actually, there were a number of markets, which had a great variety of foods (including 5,000 to 10,000 head of cattle weekly):

“The markets are not such as a town of great wealth and magnitude might be expected to possess. …. The shambles in Deansgate used to be the principal resort of butchers. In November, 1827, a handsome covered market was erected in Brown-street; and in February, 1824, one was opened in London Road, for the accommodation of butchers and green-grocers. In 1828, a fish market was erected. It stands between the Market Place and Smithy Door, on the site formerly dedicated to the pillory, the stocks and the whipping post. The butter market used formerly to be held in an area near Smithy Door, the approach to which was by a dark passage. The old surrounding buildings are now pulled down, and the market is removed to Brown-street. Adjoining the shambles in Deansgate is a small market (of a more modern construction) for fruits, &c. The great cattle market is held in a large area in Shudehill, called Smithfield. It is greatly resorted to, the weekly sale of cattle averaging from 5,000 to 10,000 head (*). The cattle market is held on Wednesday, and on other days Smithfield is occupied by traders in a variety of commodities. The number of carts with farm produce which come from every side of the country early on the Saturday morning, is truly astonishing ….. The potato market was at the same time [1804] transferred to Shudehill, to the contiguous market of St. John’s, but is now held at Smithfield.”

(*) Error in the book, should be «500 to 1,000 head»

(James Wheeler, Manchester: Its Political, Social and Commercial History, Ancient and Modern, 1836; pp. 347-348)

But the individual persons did not buy their meat in the markets, as these were wholesale, but in small butcher’s shops. There were 550 butcher’s shops in the Manchester conurbation in 1841.13 See a complete alphabetical directory in the Supplementary Files. But anyway, it is impossible to build an image in the mind, of the “migration”; this would be a mass of 50,000 persons (a football stadium), simultaneously crossing the town, … with its bad streets.

13Pigot & Co.’s ….. Directory of Yorks, Leics, …Great Manufacturing Towns of Manchester and Salford (London and Manchester, 1841), pp. 733-735.

(Pigot and Co., National Commercial Directory for 1828-9)

As to the consumption of meat, we have a report from the Manchester Statistical Society, that the consumption of butcher’s meat in the Manchester conurbation in 1836 was 100 pounds per person per year (34,700,000 pounds divided by 343,000 persons). They calculated this figure using the reports of the toll offices at the entrances to Manchester, and checking this against the sales in the butchers’ shops:

To these figures should be added the consumption of bacon, pork, fish and poultry.

On the other hand, these are weights “on the bone”, thus the edible part of the animal was 30 % less.

(Benjamin Love, Manchester as it is, Manchester, 1839, p. 159)

[Original text: W. McConnel, An attempt to ascertain the quantity of butchers’ meat consumed in Manchester in 1836, read in 1837; Manchester Statistical Society Papers, 1837-1861, p. 51: text now not findable]

The amount of meat consumed weekly by a typical workman and his family in Manchester in 1849, was 5 lb. of butcher’s meat and 2 lb. of bacon. These cost 4 shillings out of a total income of 30 shillings per week.

David Chadwick; On the Rate of Wages in Manchester and Salford, and the Manufacturing Districts of Lancashire, 1839-59, Table (DD), p. 35, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2338478

VIII. Different Levels of Housing in Manchester

Engels informs us that all the districts of Manchester (apart from the mansions of the wealthy, on the outskirts of the town), were uniformly poor, dirty, with dirty water and excrement in the streets, and with houses with small rooms and people living in cellars. But the truth is that there was a great differentiation in the housing for the working class.

“Of the first or lowest class, averaging 1s. 3d. per week rent, the occupants are of the poorest description of persons, paying frequently one-fourth of their income for rent; by which the landlords or owners realize about eight per cent net on the outlay; whilst the dwellings are without ovens or boilers, and are often filthy, damp, and unfit for habitation; generally deficient of privies, or drainage; or, in manufacturing towns, one privy to 10 or 15 houses.

The second class of dwellings are occupied by a better class of labourers, paying about one-sixth of their incomes for rent; producing, perhaps, 8 ¾ per cent to the owners as interest on their capital; and although many of them are very defective, as regards drainage and privies, they are still much better provided than the class before described; and many of them have ovens or boilers.

Of the third or best class, the occupants being generally more skilled and a better class of workmen, whose rent amounts to about one-eighth of their income, producing 9 ¾ per cent on the outlay to the owners; and here we find far superior accommodation and comparatively comfortable dwellings, well drained, and provided with privies; frequently gardens, and in most of them ovens or boilers.

These results confirm the lamentable fact, that the lower the poor are reduced in the social scales, the more they are subject to imposition and extortion.

The cottages erected by the manufacturers, and other respectable owners of cottage property, are very superior in every respect to those built or purchased by avaricious speculators, whose sole object is gain, and who enforce the payment of their rents with rigid severity. They are moreover commodious, clean, white-washed, and in many cases have the advantage of school-houses.”

(Poor Law Commissioners, Local Reports on the Sanitary Condition of the Population, 1842; 17. Lancashire, Cheshire, Derbyshire and Staffordshire, p. 247)

The 24 unions included in the list above comprised, according to the census of 1831, a population of 663,890. Lowest class (of the descriptions above) were 37,119 cottages (estimated 167,035 persons), second class were 46,050 cottages (207,225 persons), third class were 26,322 cottages (118,449 persons). The total was 109,491 cottages (492,709 persons).17

16Poor Law Commissioners, Local Reports …, 17. Lancashire, Cheshire, Derbyshire and Staffordshire, p. 247.

17Ibid., p. 244

(Poor Law Commissioners, Local Reports on the Sanitary Condition of the Population, 1842; 17. Lancashire, Cheshire, Derbyshire and Staffordshire, p. 242)

IX. Poor Areas of the City

The better classes, when they talked about “the poor”, did not mean “the totality of the working class”. For them, “the poor” were those persons who were objectively poor, that is, did not earn enough to eat properly, or were unemployed, or had very bad living conditions. The majority of workers were referred to as “the labouring classes” or “the factory operatives”, and were able to eat enough. In all the manufacturing towns, the really poor lived in clearly defined areas.

M. Faucher in 1844 mentioned “the poor quarters of the town – Angel Meadow, Garden-Street, Newtown, St. George’s Road, Oldham Roads, Ancoats, and Little Ireland. …” (Léon Faucher, Manchester in 1844: Its Present Condition and Future Prospects, 1844, p. 27)

Herr Johann Georg Kohl made visits to several parts of Manchester, including the poor parts near the rivers Irk and Irwell. “Sometimes the work-people of each manufactory form a little community by themselves, living together in a neighbourhood in a little town of their own [probably he means Ancoats]; but in general they occupy particular quarters of the town, which contain nothing but long unbroken rows of small low dirty houses, each exactly like the other. These quarters are the most melancholy and disagreeable parts of the town, squalid, filthy and miserable, to a deplorable degree.” (Kohl, Reisen in England und Wales, 1844, p. 133)

Mr. Nassau Senior, a politician who was a firm proponent of the New Poor Law, visited Manchester on a fact-finding trip. He was steered in the right direction: “The difference in appearance when you come to the Manchester operatives is striking: they are sallow and thinner. But when I went through their habitations in Irish Town, and Ancoats, in Little Ireland, my only wonder was that tolerable health could be maintained by the inmates of such houses.”

(Senior, Nassau W., Letters on the Factory Act, as it affects the Cotton Manufacturer;Addressed to the Right Honourable The President of the Board of Trade; London, 1837; p. 16)

“Several of the habitations of the Manchester poor are low, damp, ill-ventilated, and surrounded with filth. This is especially the case in Little Ireland, and the neighbouring district, which is chiefly inhabited by Irish. This, however, the most destitute part of the population, does not in general work in factories; but it would be a great improvement in their condition if they did, as the worst room in a factory is a palace of health and comfort in comparison with their miserable dwellings. The factory workmen are usually in a very comfortable condition, many of their houses displaying neatness, and even elegance in their arrangements; and when I visited them at dinner-time, the occupants were generally eating fresh meat and potatoes.”

(Factories Inquiry Commission, Supplementary Reports, Part I, 1834; D2 Lancashire District, Report by Mr. Tufnell, p. 204)

The rapporteur for Manchester to the Poor Law Commissioners in 1842, Dr. Howard (Physician to the Ardwick and Ancoats Dispensary), made it clear that, although there were really horrible districts in Manchester, these were confined to a small number of regions.

“That the filthy and disgraceful state of many of the streets in those densely populated and neglected parts of the town where the indigent poor chiefly reside, cannot fail to exercise a most baneful effect on their health, is an inference which has fully proved to be well founded; and no fact is better established than that a large proportion of the cases of fever which occur in Manchester originate in these situations.”

(Poor Law Commissioners, Local Reports, 1842, Lancashire, p. 305)

“It appears to me to be unnecessary to lengthen this report by specifying the particular localities in which nuisances, productive of malaria, tending injuriously to affect the health of the inhabitants, and to promote the prevalence of contagious diseases, exist; but it may be well to mention a few of the streets which, either from being unpaved, or without drains, or containing collections of refuse, &c., or being over-crowded and ill ventilated, have been remarked to be particularly unhealthy.” (ibid., p. 312)

“These two districts [Ancoats and Angel Meadow] are very densely populated, principally by hand-loom weavers and the workpeople employed in the factories, a large proportion of whom are Irish, living for the most part in a state of extreme indigence, and without the least attention to cleanliness. Altogether they comprehend by far the worst quarters of the town both as regards the wet and filthy state of the streets, the dirty, damp and dilapidated condition of the houses, and the improvidence, poverty, and destitution of the inhabitants; and, as might be anticipated, they furnish the great bulk of our fever patients.”

(ibid., pp. 313-314)

“Of the 1042 patients admitted into the House of Recovery [the Fever Hospital] from the 31st May, 1838, to the 31st May, 1839, 276 came from Ancoats district, 320 from Angel Meadow district, 104 from the Collegiate Church district, 141 from Bank Top district, 134 from Deansgate district, and 67 from Salford.”

(ibid., p. 316)

X. Health and Hospitals

| “Another source of physical mischief to the working class lies in the impossibilty of employing skilled physicians in case of illnesses. It is true that a number of charitable institutions strive to supply this want, that the infirmary in Manchester, for instance receives or gives advice and medicine to 2,200 patients annually. But what is that in a city in which, according to Gaskell’s calculation, three-fourths of the population need medical aid every year? English doctors charge high fees, and working-men are not in a position to pay them.” (Chapter 5, Results, p. 69) |

The men with continuous employment, covered their costs of medical care with deposits in the benefit societies, i.e. self-funded insurance contracts.

‘There is a description of mutual support among the operatives of this town, which tends materially to alleviate the pressure of the times. We allude to the numerous benefit societies in existence. These societies are constituted for the purpose of affording relief to the operative when out of employment through sickness, and to provide the means for his decent interment in case of death. The precise number of these societies it is difficult to arrive at. … In the savings bank in Manchester, the accounts of upwards of 183 such societies are kept; and they have each an average amount on hand of 83 pounds. From inquiries made at the various banks in town, we arrive at the conclusion, that there are not, on a moderate computation, less than 500 such societies in Manchester.’26

26Benjamin Love, The Hand-Book of Manchester (Manchester, 1842), pp. 109-110.

The above description is not complete. Generally, the Benefit Society had a contract with a given doctor, who would give advice and medicines to the sick persons, and who himself was remunerated by the funds of the Society.

“Attached to the institution are six physicians and six surgeons, who, being chosen by ballot from several candidates, by the whole of the trustees, may fairly be supposed to be of the highest medical talent and respectability; and thus, by means of this excellent institution, the poor have secured to them, the first scientific skill. Besides the above-mentioned medical officers, there are visiting apothecaries, and a resident surgeon and apothecary.”

(Benjamin Love, the Hand-Book of Manchester, 1842, p. 120)

Although only 2,200 in-patients were treated yearly, there were a large number of out-patients and home patients:

86 operations were carried out in the period from April 1840 to January 1841.

The hospital gave service only to the poor, but this was without charge. This was possible because the capital costs of the hospital were covered by the original subscription, the running costs were covered by the yearly subscriptions from the better classes, and the doctors worked without making a charge.

Once a patient was recommended by a subscriber, he or she applied for admission to the hospital, with admissions occurring every Monday on a weekly schedule. Patients were supposed to be known to the subscriber as well as being indigent. Subscribers discovered to be recommending patients who could afford to pay for their own care were chastised. The problem with this system was that the working poor were unable to receive medical care, since they could conceivably pay for it.

“The hitherto increasing duration of life in England is no disproof of this latter remark. It is to be accounted for, among other causes, by the extraordinary improvements which have taken place in medicine, and all its collateral branches, within the last eighty years, by the gratuitous medical aid now almost universally afforded to the poor, which places, them in this most important particular, on a level with the rich; and, not least, by the increase which has taken place in the means of subsistence – a circumstance that has been singularly favourable in the rearing of healthy children.”

(John Roberton, doctor, General Remarks on the Health of English Manufacturers, 1831, p. 10)

We return to the above-mentioned Second Report … State of Large Towns and Populous Districts, 1845, and its Questionnaire no. 58. ‘To what extent is medical advice or assistance sought for by the poorer classes, and how far is it afforded to them gratuitously or otherwise?’

Of the 23 medium and large towns who answered the Questionnaire, all of them confirm that the poorer classes receive the medical care gratis; usually the individual doctors did not charge the poor persons (See annexed list of replies; the cases of Birmingham, Dudley and Bradford, include benefit societies).

The Lying-in Hospital gave midwife services at home to poor married women at the time of delivery; the nurses were trained in the hospital. Difficult cases were treated by a doctor in the hospital. In 1840 3,400 women were helped by the institution; this would be about the half of the births in the city, or three-quarters of those of working class women. The cost was about 6 shillings, which covered the payment to the nurse.

(Benjamin Love, the Hand-Book of Manchester, 1842, p. 123)

Other hospitals were: the Royal Lunatic Asylum, the House of Recovery (fevers), the Salford and Pendleton Royal Dispensary, the Chorlton-upon-Medlock Royal Dispensary, the Ardwick and Ancoats Royal Dispensary (“this institution includes in its district, nearly 100,000 souls, and a population, mostly in the humblest circumstances”), the Institution for Curing Diseases of the Eye, the Lock Hospital (venereal diseases of women), the Dispensary for Children.

There was also a Medical School, legally authorised to extend degree certificates.

XI. Geography of Manchester

Engels makes a number of mistakes as to the descriptions of some parts of Manchester:

| “Farther down, on the left side of the Medlock, lies Hulme, which properly speaking is one great working-people’s district, the condition of which coincides almost exactly with that of Ancoats; the more thickly built-up regions chiefly bad and approaching ruin, the less populous of a modern structure, but generally sunk in filth.” (Chapter II, Great Towns, p. 42) |

Actually it was inhabited by independent workers and small shopkeepers, and the first houses were built around 1820.

The Census of 1841 gives, for example:

Durham Terrace: calico printer, joiner, corn factor, manufacturer, timber merchant

Trade Directories in 1845 give in Stretford Road: builder, grocer & tea dealer, boot maker, earthenware dealer, butcher.

We see that Hulme was being gradually built up, because in 1841 there were not yet any inhabited houses in Stretford Road, registered in the Census.

(Birley Fields, Hulme, Community Excavation, Oxford Archaeology North, Manchester Metropolitan University, June 2012, p. 11.)

The case of the movement of the better class of workers, shopkeepers, and mechanics from the Township of Manchester to the new suburb of Hulme in 1825 to 1860 is illustrative of the improvements. Hulme was laid out on a rectangular plan, the streets were wide, the houses were new and each had a privy in the back-yard, there were no inhabited cellars, the inhabitants were of decent occupations, and the suburb did not have any factories – with coal smoke – nearby.

(Second Report on the State of Large Towns, 1845, Appendix, pp. 106-116).

Parliament Bill 1825 Improvement Township Hulme

“… for while Pendleton, Hulme (a newly-peopled township), and the parts of Chorlton-upon-Medlock, and of Ardwick, bordering on the Medlock, are occupied by the skilled or best-paid labourers, …

(op. cit., p. 106)

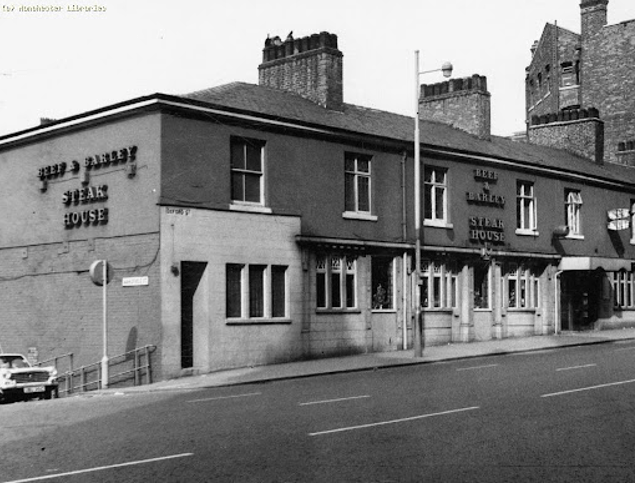

One of the worst parts of Manchester, as regards poverty, violence, housing overcrowding, and lack of sanitation, was generally taken to be to be “Little Ireland”, on the River Medlock at the southern margin of the city. Engels gives a very negative description of these conditions. We may suppose that the qualitative description is correct, as it is “about the same level of poverty” as the report by a Sub-Committee of the Board of Health, specific to Little Ireland at the time of the Cholera Outbreak in 1831.

However, we should direct our attention to the numerical information given by Engels.

| “But the most horrible spot, (if I should describe all the separate spots in detail I should never come to the end), lies on the Manchester side, immediately southwest of Oxford Road, and is known as Little Ireland. In a rather deep hole, in a curve of the Medlock, and surrounded on all four sides by tall factories and high embankments, covered with buildings, stand two groups of about two hundred cottages, built chiefly back to back, in which live about four thousand human beings, most of them Irish. The cottages are old, dirty, and of the smallest sort, …. But what must one think when he hears that in each of these pens, containing at most two rooms, a garret and perhaps a cellar, one the average twenty human beings live; that in the whole region, for each one hundred and twenty persons one usually inaccessible privy is provided; …” (Chapter II, “The Great Cities”, p. 41) |

- the houses were not old, they were only built in 1821-1824 (see 1821 map by Pigot, and 1824 map by Swire);

- only the lower group of houses was in a hole (20 feet deep), which was a level area on the bank of the Medlock; the upper group gave on to a road which ascended to Oxford Road;

- the lower group was not “surrounded on all four sides by tall factories and high embankments”; on the north-west and north-east there were no buildings, on the south there was the river (which sometimes flooded the area), and on the west there was a small mill and a gasometer;

- the upper group did not have any industrial buildings nearby;

- the total population of the area was 1510, according to the Census of 1841; as there were in total 201 houses, the density was 7.5 per house;

- population of the lower block was 381, in 61 houses, which gives 6.2 per house, and the population of the upper block was 1129, in 140 houses, which gives 8.1 per house;

The houses were all of two stories, with rooms of 13 feet square, with the exception of those of the block on Oxford Road, which were 13 feet by 26 feet (see Ordnance Survey, Manchester and Salford, 1849/1851, 5 feet to the mile, Sheet 33).

[The block on Oxford Road, i.e. the last one to the east, still exists, in the form of “The Grand Central Pub”. If we look at it today, we should construct in our mind, that here were 8 domiciles for probably 80 persons (generally, more than one family per housing unit).

Commercial name of “Beef & Barley Steak House” in 1970. We see the first five housing units. All extend 26 feet to the back of the block.]

Bolton

His description of Bolton also has some errors, … although he was used to visiting the town [?]

| “Among the worst of these towns after Preston and Oldham is Bolton, eleven miles northwest of Manchester. It has, so far as I have been able to observe in my repeated visits, but one main street, a very dirty one, Deansgate, which serves as a market and is in even the finest weather, a dark unattractive hole in spite of the fact, that, except for the factories, its sides are formed by low one and two-storied houses. Here, as everywhere, the older part of the town is especially ruinous and miserable.” (Chapter II, “The Great Towns”, p. 30) |

The fact was, there were about twenty wide and straight streets (see Ordnance Survey, Bolton, 1847/1849, 5 feet to the mile, Sheets 6, 8, 9, 12, 13)

Deansgate, according to an engraving of 1840, was clean and open to the sky.

Deansgate looking east c.1840; 5-7 Deansgate is still visible today (from an engraving in the Bolton Archives collection)

www.bolton.gov.uk/conservationareas

The Potteries

| “North of the iron district of Staffordshire lies an industrial region to which we shall now turn our attention, the potteries, whose headquarters are in the borough of Stoke, embracing Henley, Burslam, Lane End, I.ane Delph, Etruria, Coleridge, Langport, Tunstall and Golden Hill, containing together 60,000 inhabitants. The Children’s Employment Commission reports upon this subject that in some branches of this industry, in the production of stoneware. the children have light employment in warm, airy rooms; in others, on the contrary, hard, wearing labour is required, while they receive neither sufficient food nor good clothing. Many children complain: “ Don’t get enough to eat, get mostly potatoes with salt, never meat, never bread, don’-t go to school, haven’t got no clothes.” “ Haven’t had nothin’ to eat to-day for dinner, don’t never have dinner at home, get mostly potatoes and salt, sometimes bread.” “ These is all the clothes I have, no Sunday suit at home.”” [apparently Interviewee No. 14, William Hell, aged 13] (The Remaining Branches of Industry, pp. 137-138) |

We have a large amount of information about the life of the workers – adults and children – in the Potteries in 1841, from the report of Dr. Samuel Scriven to the Commissioners of the Children’s Employment Commission [the source used by Engels]. He specifically collected and commented data as to the possible dangers to the children from: handling materials and products with a lead/arsenic content, long hours, employment from an early age, walking long distances daily to take the ware from the workshop to the kilns, exposure to extreme differences in temperature and excessive currents of air. The handling of materials and products with a lead content also affected the adults. The report includes 330 interviews with children, adult workers, adults who supervise the children in their workrooms, administrators and owners of factories, clergymen, doctors, principals of schools, and a police chief. He visited, and took interviews, in the majority of the factories.

(Samuel Scriven, Report to Her Majesties Commissioners on the Employment of Children and Young Persons in the District of the Staffordshire Potteries; and on the actual State, Condition, and Treatment of such Children and Young Persons, House of Commons, Children’s Employment Commission, 1841)

But the living conditions of the workers (adult and children) were good.

“The operatives are in their general character a quiet, orderly people, possessing not only the necessaries, but in most instances the comforts and luxuries of life; their habitations are respectable, cleanly, and well furnished.” (p. B 2, note 11).

“Their wages are considered the best of any staple trade in the kingdom.” (p. C 4, note 12)

In his first page, he notes that that the sales volume at the date of his report is very much lower than in an average year:

“Perhaps no time or period of the year could have been more unfortunate than that which I have been engaged,- first because the monied and commercial interests of America, a country of which the welfare of this district so much depends, has been such as to create fearful anticipations and an extraordinary depression of the trade, by which thousands have been thrown out of employ. In the second place, manufacturers availing themselves of this (it is to be hoped, temporary evil) have allowed workpeople to absent themselves during the Christmas season, by which they have been enabled to nurse their orders for a future day. Thirdly, the intensity of the frosts was such as to obstruct the navigation of the canals by which they receive and transmit their materials and goods, thereby compelling them to suspend every operation of potting.” (page C1, note 6)

The persons interviewed by Dr. Scriven are 330 in total, 117 adult workers (incl. room supervisors), 126 children of age 14 or less, 87 “professional persons” (owners, administrative office, priests, schoolmasters/-mistresses, teachers, magistrate, police superintendent). The professional persons would appear to be the totality of this group in the Potteries region.

As to food, 22 of the children report that they eat beef or bacon with ‘tatoes daily; 13 sometimes beef or bacon with ‘tatoes; 2 could eat more; several eat as much as they want. No boy or girl makes a complaint about the quantity of the food. Those who work in painting and in transfers, bring their food every day, and heat it at midday on the oven.

The use of the “slip” (solution of clay with lead and arsenic added, in small quantities) which was painted onto the ware, did cause grave problems to the men; a few had died in the previous years, and some had a paralysis of an arm or a whole side of the body, while others had problems in the stomach and intestines. It appears that those men who washed their arms well after working, and covered themselves properly, did not suffer these problems. The boys did not suffer much from the “slip”. The excessive walking each day did make them very tired when they went to bed, and they were in general thin. The effect on the men of working very long hours, added to the extreme distances that they walked when they were children, is seen from the fact that from 1840 to 1860, the adult men on average lost two inches of height.

The children who are employed in painting, flower-making, moulding and engraving have an easy life. These are girls from 8 to 17 years old, and boys from 14 to 17. “They are seen sitting at their clean tables, at a comfortable distance from each other, and in an airy, commodious, and warm room, well ventilated, and heated by a stove or hot plate, on which they dress their meals. The women who superintend their work are generally selected from among the rest on the premises on account of their good moral conduct and long servitude. They commence their duties at six in the morning in summer, and at seven in winter, and leave at six. In the midst of their occupations (which have in reality more the character of accomplishments) they are allowed the indulgence of singing hymns. I have often visited their rooms unexpectedly, and been charmed with the melody of their voices. In personal appearance they are healthy, clean, and well conducted.” (p. C 4, paragraph 14)

14 of the children interviewed say spontaneously that they like their work (these are not only the painting and engraving children). Those that work with the “slip” say that it has not hurt them yet. Nearly all the mould-runners say that they go to bed very tired. The children’s way of expressing themselves gives the idea that they have had to grow up quickly.

The boys say that they are never hit by the men that they work for. This is confirmed by men and women who supervise the rooms where the boys and girls work. This is clearly due to the fact that the owners are very decent persons, generally practicing Methodists. One of the supervisors says “… on the whole there cannot be better masters”. Dr. Scriven, at the beginning of his report, writes “The manufacturers are a highly influential, wealthy, and intelligent class of men: they evince a warm-hearted sympathy for those about them in difficulty or distress, contribute as much as possible to their happiness, and are never known to inflict punishments on the children, or allow others to do so.” (p. C 2, point 7)

But sometimes the owners were too good:

“It is the custom here sometimes to lend money to the people if in distress, and deduct the amount by instalments from the parents themselves or wages of the children. Master has often lost money by this when meeting with unprincipled men.” (William Griffith, Interviewee No. 35)

There was a large amount of drunkenness in the towns, as the workers had a lot of spare money.

XII. Unfounded accusations against progressive mill-owners

Engels first accepts that the “country manufacture” gives healthy jobs, good wages, and nice cottages to their employees. But he then accuses the owners of hypocrisy, of exercising control over the employees, and that there “may be” a truck shop in the neighbourhood.

Note that the accusations are formulated in such a way, that they cannot be disproved.

| “You come to Manchester, you wish to make yourself acquainted with the state of affairs in England. You naturally have good introductions to respectable people. You drop a remark or two as to the condition of the workers. You are made acquainted with a couple of the first Liberal manufacturers, Robert Hyde Greg, perhaps, Edmund Ashworth, Thomas Ashton, or others. They are told of your wishes. The manufacturer understands you, knows what he has to do. He accompanies you to his factory in the country; Mr. Greg to Quarrybank in Cheshire, Mr. Ashworth to Turton near Bolton, Mr. Ashton to Hyde. He leads you through a superb, admirably arranged building, perhaps supplied with ventilators, he calls your attention to the lofty, airy rooms, the fine machinery, here and there a healthy-looking operative. He gives you an excellent lunch, and proposes to you to visit the operatives’ homes; he conducts you to the cottages, which look new, clean and neat, and goes with you into this one and that one, naturally only to overlookers, mechanics, etc., so that you may see -”families who live wholly from the factory”. Among other families you might find that only wife and children work, and the husband darns stockings. The presence of the employer keeps you from asking indiscreet questions; you find every one well-paid, comfortable, comparatively healthy by reason of the country air; you begin to be converted from your exaggerated ideas of misery and starvation. But, that the cottage system makes slaves of the operatives, that there may be a truck shop in the neighbourhood, that the people hate the manufacturer, this they do not point out to you, because he is present. He has built a school, church, reading-room, etc. That he uses the school to train children to subordination, that he tolerates in the reading-room such prints only as represent the interests of the bourgeoisie, that he dismisses his employees if they read Chartist or Socialist papers or books, this is all concealed from you. You see an easy, patriarchal relation, you see the life of the overlookers, you see what the bourgeoisie promises the workers if they become its slaves, mentally and morally. This “country manufacture” has always been what the employers like to show, because in it the disadvantages of the factory system, especially from the point of view of health, are, in part, done away with by the free air and surroundings, and because the patriarchal servitude of the workers can here be longest maintained. Dr. Ure sings a dithyramb upon the theme. But woe to the operatives to whom it occurs to think for themselves and become Chartists! For them the paternal affection of the manufacturer comes to a sudden end. Further, if you should wish to be accompanied through the working-people’s quarters of Manchester, if you should desire to see the development of the factory system in a factory town, you may wait long before these rich bourgeoisie will help you! These gentlemen do not know in what condition their employees are nor what they want, and they dare not know things which would make them uneasy or even oblige them to act in opposition to their own interests. But, fortunately, that is of no consequence: what the working-men have to carry out, they carry out for themselves.” (Text not present in the English version of Mrs. Wischnewetzky; in the German version of 1848, see the footnote with asterisk in page 227 and extending to page 228; this English translation is copied from the last page of the Chapter “Single Branches of Industry”, in the www.marxists.org version) |

The better class of the owners were generally accepted as humane and moral persons.

“The law was not passed for such mills as those of Messrs. Greg and Co., at Bollington, Messrs. Ashworths, at Turton, and Mr. Thomas Ashton, at Hyde; had all factories been conducted as theirs are, and as many other I could name are, there would probably have been no legislative interference at any time. But there are very many mill-owners whose standard of morality is low, whose feelings are very obtuse, whose governing principle is to make money, and who care not a straw for the children, so as they turn them well to money account. These men cannot be controlled by any other force but the strong arm of the law; …..”

(Nassau Senior, Letter from Mr. Horner to Mr. Senior, 23 May 1837, Letters on the Factory Act, B. Fellowes, London, 1837)

(Mr. Horner was the Chief Inspector of Factories)

But we cannot, at this distance of time, know what proportion of the mill owners treated the children well, and what proportion treated them badly.

Possibly the good mill owners were actually in the majority:

“When I entered a factory, I am bound to remark that I experienced much readiness on the part of the proprietors and of their overlookers in procuring for me ample means of making an impartial inquiry. If I am able to confide in my own observation, and in the accounts furnished to me by workpeople of every age in private conversations frequentlyrepeated, I must arrive at the conclusion, that the proprietors are generally anxious to promote the convenience and comfort of their dependents as far as the system admits; that they usually endeavour to prevent acts of harshness and of immorality; that if such cases arise, it is mainly owing to their absence, or to their neglect of personal superintendence; and that there are not a few among them who really act a paternal part, and receive the recompense of respect and gratitude. Their situation is a difficult one; but the more closely they assume the character of the observant master of a great family, and the more narrowly they investigate, appreciate, and purify the composition of their family, the more likely is every factory to become respectable and happy.”

(Factories Inquiry Commission, Second Report, 1833, Medical Reports by Dr. Hawkins, General Report respecting the Counties of Lancashire, Cheshire, and Derbyshire, D.3., p. 5)

Mr. Oldknow, owner of a large mill on the outskirts of Manchester, had a very good reputation, which was manifested at his funeral:

“Oldknow died at Mellor Lodge on September 18th, 1828, and he was buried on September 24th at Marple Church. “Few men,” says the Gentleman’s Magazine of November 1828, “who have of late quitted this transitory scene have led a life of greater industry and more active benevolence, or died more universally lamented than this individual … How he was loved and honoured is perhaps best told by the spontaneous feeling of all classes of society on that occasion. From an early hour the people began to assemble, and lined the way from his house to the Church, closing as the procession moved along. On its arrival at the gateway a line was formed by the children from the Military Asylum, each dressed in a scarlet spencer, and a black band around the arm … The funeral service was read by the Rev. Mr. Litler, The Reverend Gentleman himself was much affected and hundreds gave free vent to their feelings of real sorrow. … Probably the number assembled was not less than 3,000. As it was the general wish to see where the body was deposited, several hours elapsed before the vault was clear.””

(Unwin, George; Hulme, Arthur; Taylor, George; Samuel Oldknow and the Arkwrights: The Industrial Revolution at Stockport and Marple, 1924, pp. 234-235)

XIII. Financial and Housing Properties

According to Engels, as the workers could not save anything out of their exiguous wages, they were always in a precarious situation, and did not know if they would have money tomorrow.

| “True, it is only individuals who starve, but what security has the working man that it may not be his turn tomorrow? Who assures him employment, who vouches for it, that, if for any reason or for no reason his lord and master discharges him tomorrow, he can struggle along with those dependent upon him until he mar find some one else “to give him bread?” Who guarantees that willingness to work shall suffice to obtain work, that uprightness, industry, thrift, and the rest of the virtues recommended by the bourgoisie, are really his road to happiness? No one.” (Chapter II, The Great Towns, p. 19) |

But the better class of workers were the owners of physical and financial assets.

Many of them had houses bought in cash, or paid through mortgages.

In Bradford a large number of the workers owned their houses:

“Do many of the labouring classes own houses?” “Many of the working classes have built their own cottages; those that have saved perhaps 60 l. or 70 l. have purchased land and raised money on mortgages, and then have erected others. In some instances clubs, sustained by monthly payments, have built, and the houses are divided by valuation and lot.

“What proportion of labouring class houses are held directly or indirectly by themselves?” “I cannot state precisely; probably there might be one-third of the cottage houses owned by the labouring class.”

“Are there other classes that are wholely dependent on cottage rent?” “Yes; I know several who sink all their capital in cottages, and depend on the rent.”

(Report of the Commissioners on the State of Large Towns and Populous Districts, 1845, Vol. 2 p. 183; Bradford, Dwellings of the Working Classes, evidence of Mr. Joseph Farrar, one of the Secretaries of the Mechanics’ Institute)

“The more providential amongst them [potters] work six days in the week, twelve hours each day, and the miserly and penurious more than that, and get a great deal of money. Perhaps there is no manufacturing district in the kingdom where so many freeholds are held by working men – one whole street, called Hot-lane, is possessed exclusively by them, in this immediate neighbourhood.”

(Samuel Scriven, Report to Her Majesties Commissioners on the Employment of Children and Young Persons in the District of the Staffordshire Potteries; and on the actual State, Condition, and Treatment of such Children and Young Persons, House of Commons, Children’s Employment Commission, 1841; interviewee 204, Mr. Godwin, Principal)

Many of the houses in Manchester were built by people who used a flimsy form of construction in order to get out a maximum of profit from the property. The houses were built at a minimum cost, without cellars or foundations, and with walls of only half a brick thickness.

But the investors were not rich people, but “building clubs”, whose members were workers with good earnings and tradespeople. There had been possibly 150 of these clubs in Manchester and nearby towns since the commencement; if each club had 100 “investors” at 100 pounds each, this would correspond to a total of 1,500,000 pounds. At 60 pounds cost of construction each, this would be 25,000 houses which had been built with this scheme.

The members paid 10 shillings per month, thus every 2 months the club had 100 pounds to start a building. This shows us that there were a good number of working-class men who could save 10 shillings a month, and also had taken the decision to use this amount in an “investment”. A person who wanted to build at this moment on a given lot, could take up all the money for the house, and contract to pay the money in the following months to his co-investors. The payments for the house were assured by a mortgage on the house.

(Poor Law Commissioners, Local Reports on the Sanitary Condition of the Population, 17. Lancashire, Cheshire, Derbyshire and Staffordshire, 1842, pp. 240-241)

(J. T. Slugg, Reminiscences of Manchester Fifty Years Ago, J. E. Cornish, Manchester, 1881; Chapter XXV, Building Clubs)

“The Manager of the Manchester Savings’ Bank, (and on the best grounds he formed his opinion) has stated that there is as much money annually invested in building clubs in Manchester, as in the Saving Bank.” (p. 111)

The main instrument for saving money was the government-administered Savings Bank. Only the members of the working classes could invest in these (limits on yearly deposit amounts and on net balance), but husbands and wives could have separate accounts.

We do know how much money “the people” had saved up. In 1849 in the savings banks there were 1,100,000 depositors from all the United Kingdom with a total amount of 28.5 million pounds. The number of depositors increased from 370,000 in 1830 to 1,100,000 in 1849. With a total population of 18,000,000 [1841] and 5 persons per family, this means that 30 % of the families in the United Kingdom had money in excess of their expenses, of about 26 pounds or 520 shillings each accumulated, when the average weekly income for a working-class family in good circumstances was 25 shillings.

(George Porter, The Progress of the Nation: …, 1851, Increase of Personal and Real Property, pp. 612-613)

In the year 1844, there were 20,680 working class families with a deposit account in the Manchester and Salford Savings Bank. The total deposit amount was 568,000 Pounds, the amount deposited in the year was 188,000 Pounds, and the withdrawals were 126,000 Pounds.

David Chadwick; On the Rate of Wages in Manchester and Salford, and the Manufacturing Districts of Lancashire, 1839-59, Table (CC), p. 34, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2338478

The Manchester and Salford Savings Bank was situated at the corner of Cross Street and King Street. Engel’s offices were on Deansgate, where the House of Fraser is now. The distance is about 200 yards, so he must have known where the bank was.

There were also benefit societies, building societies, and unemployment clubs.

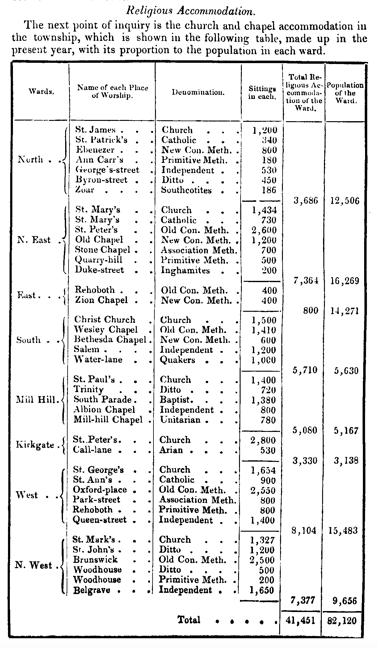

XIV. Supposed Indifference to Religion

| “His faulty education saves him from religious prepossessions, he does not understand religious questions, does not trouble himself about them, knows nothing about the fanaticism that holds the bourgeoisie bound; and if he chances to have any religion, he has it only in name, not even in theory. Practically he lives for this world, and strives to make himself a home in it. All the writers of the bourgeoisie are unanimous on this point, that the workers are not religious, and do not attend church. From this general statement are to be excepted the Irish, a few elderly people, and the half bourgeoisie, the overlookers, the foremen and the like. But among the masses there prevails almost universally a total indifference to religion, or at the utmost, some trifling Deism too underdeveloped to amount to more than mere words, or a vague dread of the words infidel, atheist, etc.” (Chapter V, Results, p. 84) |

According to the Religious Census of 1851, in Manchester there were 105,000 sittings for a population base of 303,000, in Liverpool there were 176,000 sittings for a population base of 375,000, and in Leeds there were 81,000 sittings for a population base of 172,000 (pp. 121-124). [A “Sitting” was the attendance of one person on a typical Sunday, as reported by the priest to the Census authorities]. The given numbers of sittings arithmetically cannot be only the better classes, but must include also a large segment of the working classes.

In Manchester in 1851 there were 32 Church of England buildings, 19 Independents, 17 Wesleyan Methodists, 10 Wesleyan Association, 7 Roman Catholic, 4 Unitarians, 1 Society of Friends, 5 Primitive Methodists, and 2 Jewish Synagogues.

There was also a Town Mission for Manchester, which carried out activities intermediate between the present-day “Jehovah’s Witnesses” and the Salvation Army.

The active people came from the Church of England, Methodists, Independents, Presbyterians and Moravians. According to their report of 1841, they had held five thousand meetings, in which one hundred thousand people heard the Gospel. (pp. 148-151)

We have a useful information of the distribution of worshippers in Leeds in 1839:

(Statistical Committee of the Town Council, Report upon the Condition of the Town of Leeds and of its inhabitants. 1839, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2338052, p. 397.)

“In dividing the accommodation according to the sects, we see that there are 9 churches belonging to the Establishment, containing 13,235 sittings; 3 Catholic chapels, with 1,970 sittings; 17 Methodist chapels, with 16,340 sittings; 6 Independent chapels, with 6,030; and 5 belonging to other sects, and containing 3,876 sittings.

The distribution of the accommodation is very unequal. In the North, North-east, and East wards, which are inhabited chiefly by the labouring classes, there are only 11,850 sittings for a population of 43,046 individuals, while in the other and more opulent wards there are 29,601 sittings for 39,074 persons.

[The low proportion for the North, North-east and East wards, may be due to the fact that only two churches were built in this geographical area; but even so, this is a proportion of 25 %, not zero.]

The remaining institutions of a religious character existing in the town are, the Religious Tract Society, the Leeds Branch Missionary Society, the Leeds Ladies’ Branch Bible Society, the Leeds Auxiliary Bible Society, the Auxiliary Methodist Missionary Society, the District Committee for Promoting Christian Knowledge, the Association in aid of the Moravian Mission, the Auxiliary Hibernian Society, with a few others.”

XV. Physical Aspect of the Workmen

The workers in Manchester were, since the beginning of the century, known for being short and of sallow countenance.

“A recruiting officer testified that operatives are little adapted for military service, looked thin and nervous, and were frequently rejected by the physicians as unfit. In Manchester he could hardly get one of five feet, eight inches; they were usually only five feet, six to seven, whereas in the agricultural districts, most of the recruits were five foot eight.” p. 107

Factories Enquiry Commission, First Report, 1833, Mr. Tufnell’s Evidence, p. 59.

“It is perfectly true that the Manchester people have a sickly, pallid appearance; but this is certainly not attributable to factory labour, for two reasons: first, because those who do not work in factories are equally pallid and unhealthy-looking, and the sick society returns show that the physical condition of the latter is not inferior:- secondly, because the health of those engaged in country cotton factories, which generally work longer than town ones, is not injured even in appearance … Mr. Wolstenholme, surgeon at Bolton, says that “the health of factory people is much better than their pallid appearance would indicate to any person not intimately concerned with them.””

(Factories Inquiry Commission, Supplementary Report … as to the Employment of Children in Factories, 1834, Part I, Mr. Tufnell’s Report from Lancashire, p. 198)

| “The result of all these influences is a general enfeeblement of the frame in the working- class.” (Chapter V, «Results», p. 70 |

Edwin Chadwick reports that the members of the labouring class had in the 1830’s and 1840’s, strong bodies, and certainly stronger than those of workers in France and Germany: